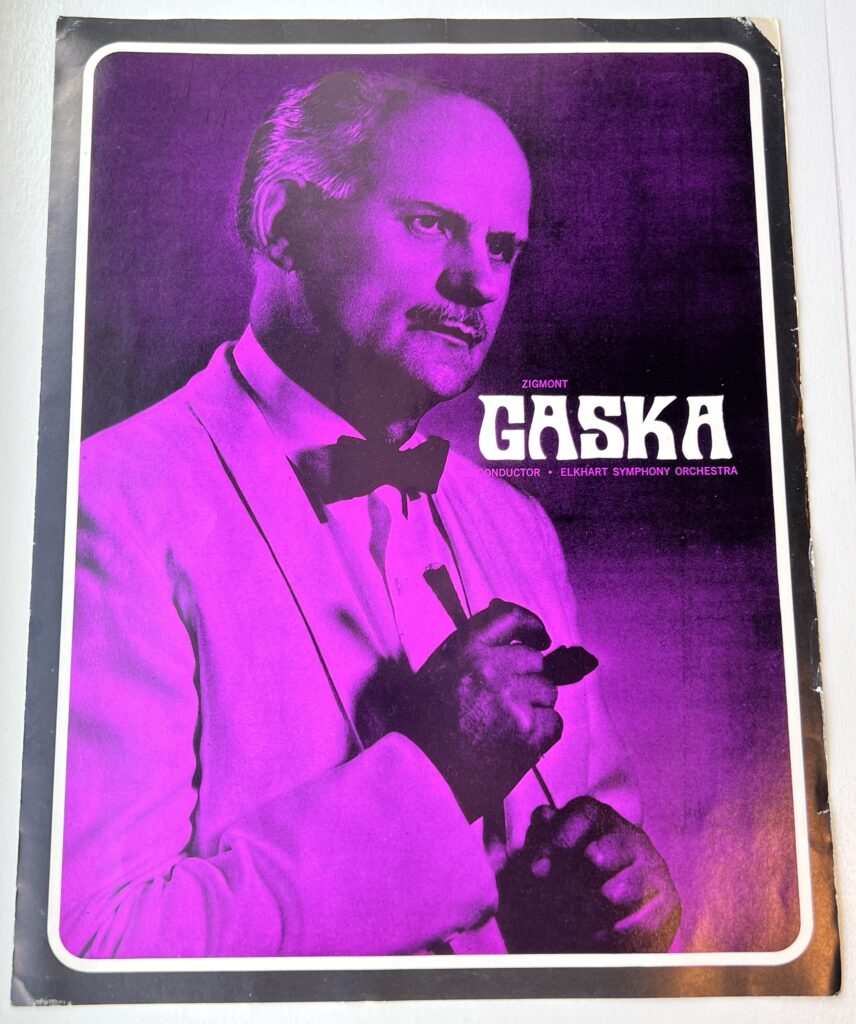

Maestro ensured Elkhart would live up to its instrument legacy

The hometown of the world’s musical instrument industry had no orchestra to call its own until Zigmont George Gaska made it happen.

He was no corporate titan. No building around town bore his name. Gaska simply loved music and wanted to share its beautiful grace and unifying power.

“Zigmont George Gaska has had a mission,” said the Rev. Carl Hager, a University of Notre Dame professor emeritus, at a 1982 tribute. “… In spite of many obstacles, all the usual roadblocks to progress in the arts, he was able to make things happen musically, with gentle persuasion, reaching out for the help and cooperation of many people, and getting it. We have been enriched by his genial and beneficial musical presence.”

The Elkhart County Symphony Orchestra was born in 1948, and Gaska held the conductor’s baton for decades. Never blessed with robust finances, the Symphony struggled through increasingly lean times after his retirement in 1978 and death in 1996.

For 45 days in 2005, the community heard the orchestra had played its last note. Dedicated musicians made quick moves to “Save Our Symphony.“ Still channeling the spirit of its founder, the group committed to make fine music approachable by all in every corner of the county.

Just as Gaska would have wanted.

“My hope and wish is that my life and work,” Gaska wrote in his autobiography, “founding musical groups, playing with and for others, teaching, conducting, repairing string instruments – will continue through each life I have touched to enrich further generations. That is my memorial!”

Brilliance on violin

First and foremost, Gaska was an accomplished musician.

With no sheet music available, he learned to play the pump organ by imitating his mother. As an 8 year old, he received a violin for Christmas 1916 and found the melody right away.

“Now and then,” a Conn Band Instrument Co. promotional flier from the 1970s stated, “a child is born who must be a musician. Such a child was Zigmont George Gaska. …

“One evening, he went to the Bucklen Theater to hear Albert Spalding, one of the world’s greatest violinists. Now Zigmont knew what the violin could do.”

Gaska studied engineering in Chicago, but kept up with his music. His brilliance on stage amazed the critics.

“When George Gaska tucked his violin under his chin to play,” according to a 1930s edition of the South Bend News-Times, quoted in Gaska’s autobiography, “he could just as easily have put the audience in the palm of his hand; it was all his.”

His talent was undeniable. But many young performers did not have the same access to opportunities. Gaska made it his life’s work to resolve that problem.

“Yes, there was an enormous interest in music with many people studying violin, piano, and other instruments,” wrote Nancy Price in the foreword to Gaska’s book. “But the institutions of music were almost non-existent and local musical performances were infrequent except for band concerts, choruses, and recitals.”

Gaska taught locally, in the classroom and through lessons. He formed the Gaska String Quartet for the first time in 1930. The South Bend Junior Symphony arrived in 1938. And – with Joseph Fischoff – the Chamber Music Society started in 1945.

He desperately wanted to bring musical opportunities to his hometown of Elkhart, though.

From classical to pop

In 1948, he met with local benefactors and instrument builders to pitch his idea for a symphony orchestra for Elkhart. The first musicians were volunteers, and the first concert was short and by invitation only.

A few months later, the Symphony was ready for its public debut at the Elkhart High School auditorium. Events mirrored Gaska’s personality – energetic sounds focused on talent and technique, but with a hint of whimsy.

“We had cabaret-style pop concerts,” Bernice Dryer, one of Gaska’s original players, told Goshen News reporter Ann Jacobson on the Symphony’s 50th anniversary in August 1998. Ruby Thomas, another musician quoted in the article, said Gaska would end the concert, “lay down his baton and dance the first dance, usually a waltz, with his wife, Mae. That was the cue that a dance band was about to begin playing the remainder of the evening.”

Gaska grew the organization from 45 musicians that first night to 85 and more. He led the orchestra for 30 years until his retirement due to health issues in 1978.

He felt his most significant accomplishment in those years was a 1971 effort to showcase Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

“Gaska believes that the Ninth Symphony has something to say to today’s world,” The Elkhart Truth’s editorial stated on April 16, 1971. “The conductor has been quoted as saying that ‘the world was not much different in 1824 than it is today in 1971. It was a time of confusion, political upheaval and racial struggle. Beethoven believed in freedom and the brotherhood of man. He fought for those ideals in his music and in his Ninth, he made the greatest plea for freedom and brotherhood.’”

Along with 200 voices in the chorus, Gaska achieved success on the stage that night in Elkhart.

For your listening pleasure

A purist, Gaska believed recorded music would never replace the thrill of live performances. “Listening to a disc,” he told Truth reporter Evelyn Schaefer for a April 12, 1963, article, “is like getting kissed over the telephone.”

This strong opinion, however, did not keep the maestro from becoming a multimedia star decades before such a term existed.

He hosted radio programs on WTRC-AM, including one called “Music You Enjoy.” On television, he brought viewers “Relax and Listen” for 30 minutes every week on WSJV.

“I would talk about music and, while playing records, sit in an easy chair and smoke my pipe,” Gaska wrote about his TV hosting duties in his autobiography. “I wanted to present music in an interesting way.”

His talents went beyond both music and the public view.

In a 1969 photo in The Elkhart Truth, Gaska appeared with a focused and thoughtful look on his face. Dressed in a flannel shirt, he held a Lectro Kleen spray can in a darkened auditorium.

“Concert-goers … now have at least some assurance that they can sit back and really enjoy the music,” the article reported. “Maestro Zigmont Gaska recently took time out of his busy teaching schedule and rehearsal schedule to do a little ‘moonlighting’ at the Sophomore Division of Elkhart High School …

“He personally took an oil can in hand and ‘doctored’ the hinges of each of the auditorium’s 1,800 seats. … He is certain that both the audience and performers will take added delight at the absence of the serenade of squeaking seats which intermittently accompanied the orchestra during concerts in the past.”

A time of change

When Zigmont George Gaska was ready to set down his baton, he handpicked his successor. Michael Esselstrom arrived with plans to grow the artistry demonstrated by the orchestra, but also improve the organization’s financial health.

“We have a community that demands performances of a high level,” Esselstrom told Truth reporter Tom Jacobs during his Sept. 14, 1978, introduction. “It’s our job to provide it.”

Two seasons later, though, the group saw a different headline hit the paper: “Costs Rise, So Symphony Is Forced to Cut Corners.” That April 28, 1980, article, announced a 20-percent increase in the price of season tickets and a bleak forecast for raising the necessary operating funds.

“Our costs are going up. We just have to raise prices,” said Robert Pickrell, Elkhart County Symphony Association manager. According to Jacobs’ reporting, “The decision to raise prices and cut back the number of concerts was made in order to avoid ‘a huge deficit in the budget,’ (Pickrell) added.”

Performance quality did not diminish in the face of budget concerns. During Esselstrom’s 20 years at the helm, grants were obtained to ensure orchestra players could inspire middle-school classrooms – a key outreach Gaska demanded when he created the group.

“Thanks to people like Esselstrom,” Truth city editor Steve Bibler wrote on April 28, 1995, “classical music is becoming more accessible to larger audiences,” evidenced by crowds for concerts approaching 1,000 attendees.

The local economy had changed plenty, though, from the days when Gaska sought the first sponsorships. Musical instrument makers were evolving and relocating, and the craftsmen became fewer in numbers. The sale of Miles Laboratories to Bayer resulted in the loss of thousands of high-skilled pharmaceutical positions.

Facing another crossroads in leadership, the Elkhart County Symphony was about to be silenced.

Saving our symphony

In the spring of 2005, Elkhart County no longer had a symphony orchestra to call its own.

Chased by mounting debts, the Elkhart County Symphony Association’s board of directors saw no future. With one vote, it was decided the organization would cease operations. The assets would be sold, the music would come to an end.

Zigmont George Gaska’s dream for an orchestra in Elkhart, the musical instrument capital, was over.

Except …

“It is a crime to lose an orchestra,” said Brian Groner, who became conductor of the Elkhart County Symphony after its re-emergence. “When an orchestra board decides to cease operations, it is often because of burnout or malaise. On some occasions, it is a lack of vision – when you’re in survival mode, it is difficult to see what you can be when things seem insuperable.”

Within 45 days of the board’s vote to close shop, a group of musicians and music lovers stepped forward. The “Save Our Symphony” committee communicated with musicians and brought together a new group of board officers.

They worked quickly.

By Oct. 31, less than six months after the move to dissolve the organization, the music played again. Season 57’s first concert, according to The Truth, was a mix of classical and pops. It was just as Gaska would have liked, music that was accessible and enjoyable for all.

“We didn’t go in with the intention to be leaders,” said Karen Braden, who has performed with the strings since 1975. “But attendance had become really small. A lot of people didn’t know the Symphony. … The arts are important to the community, and the orchestra had been going (nearly) 60 years, and we thought we owe $10,000 and we’re closing the door? We felt we had to do something.”

Community players

Musicians agreed to play for free as the orchestra regained its footing. Concert dates decreased. The youth orchestra transferred to Goshen College for nurturing and cost saving.

The climb was slow but steady.“

They worked very hard to find a way through that gap of quite a number of years,” said Groner, now retired and living in Florida, in an interview for articles celebrating the Symphony’s 75th season in 2022-23. “… So many were actively involved in shepherding the orchestra back to a stable position.”

Deb Inglefield said the Symphony couldn’t have made it through tough times without the commitment of the musicians.

“Most of them hung in with us – years of not being paid, or being paid late – and played their hearts out,” said Inglefield, the personnel manager of brass, winds and percussion, for the same anniversary article. “This really is a community group. It’s one of the things I like to think of as a selling point. You have your kids’ orchestra director, your roofing guy, a faculty member at Notre Dame – real people, real music, from this community.”

Ten years after SOS, Susan Ellington, then executive director, said the Symphony still had work to do in connecting with the community. Her perpetually positive engagement carried the organization through many of its darkest days. Sadly, she lost a fight with thyroid cancer in April 2017.

“Before Susan passed, I promised her I would do everything in my power not to let the orchestra fail,” Groner said. “She worked tirelessly. She was a magnetic person. At that time, they were just starting to turn that corner. They had made substantial progress on the path toward vibrancy.”

That is a word Gaska would have found that progress to be sweet sounding.

Sweet-sounding legacy

One of Zigmont George Gaska’s original tenets for the Symphony at its founding in 1948 was to put music in front of school children.

Classroom visits would turn into interest. Young musicians would seek lessons and practice time. And the orchestra would reap the benefits by having a growing roster of talent in the community.

It’s an idea that has continued on to this day. The Symphony players still schedule for schools. They perform in small ensembles at Elkhart Public Library’s Music in the Stacks programs.

The creator of the Elkhart County Symphony Orchestra, who died in 1996 at age 88, still seems to have a grasp of the baton.

When Gaska retired as conductor, U.S. Rep. John Brademas rose in Congress to deliver a tribute.

“His love of music, and his eagerness to share that love with those around him,” the congressman said on Feb. 11, 1980, “have made him a major force in our area.”