1969 homecoming put focus on Elkhart’s simmering race issues

The 1969 homecoming queen didn’t receive her honors during the Elkhart High School football game. The shutout victory against a South Bend team under the lights that night was hollow.

Racial tensions – long ignored and short fused – had become the story in Elkhart.

The city was blistered. It continues to carry the scars. But in the immediate aftermath of a critical 72 hours, a Black minister and the white mayor provided leadership with calming influence. Their actions made it clear this pivotal moment of truth could not – and would not – be ignored.

The stunning confrontation between Black and white Elkhart High School students led to immediate operational changes at the Elkhart Police Department. It resulted in greater community focus on communications and reconciliation in the weeks following, and eventually more programs for youth throughout the city.

Reporters of The Elkhart Truth kept a good amount of information in their files about the country’s move toward political, social and economic equality. Until Sept. 26, 1969, those carefully curated clips had datelines other than Elkhart.

The students walked out

At the beginning of the 1969-70 school year, Elkhart High School had an enrollment of 2,799, including 212 Black students.

As the September homecoming week kicked off, Black students voiced disappointment about having no representation among the 15 queen candidates. By Wednesday, they demanded the opportunity to have at least one Black candidate on the parade floats for each class.

On Thursday night, Black students attending the parade and pep rally at Rice Field sat together in one section of bleachers and were silent when the queen was announced.

While The Truth reported it appeared the event would finish without incident, “a crowd of students began gathering in the center of the parking lot and a group of three or four white students began exchanging verbal abuses with the blacks. A fight erupted between two boys, both seniors, and shortly after school officials broke it up, another scuffle started a short distance away.”

Police told the newspaper two white students were carrying chains and a third white student sprayed “a liquid chemical repellant” at Black students during the scuffle.

“Negro students told police that the same small group of white youths have been antagonists throughout school,” as reported in the Sept. 26 edition.

The next morning, as school administrators and city officials met to discuss if Elkhart should play football as planned, as many as 300 students staged a noon walkout at EHS.

School Superintendent Harold Oyer told a reporter, “I suppose the causes … were mixed. Some students felt that their walkout was a protest against one policy or another, some were genuinely afraid because of the tensions that did exist there. I can sympathize with this.”

Fight moves to the streets

Football coach Tom Kurth and his players had a locker room reckoning. At the end of the meeting, Black players assured Kurth they would continue to take the field regardless of disputes and confrontations between classmates.

The homecoming game would go on with the blessing of Mayor John Weaver, police and school administrators, but additional activities like dances and alumni gatherings were canceled and the concession stands at Rice Field were closed.

“The game itself,” The Truth reported Sept. 27, “was played without incident, although observers noted that fans were subdued.”

The heat was moving to the streets.

Racial divides common in other parts of the country, seen for several summers on televisions and read about in the newspapers, now were happening here. Elkhart’s traditionally Black neighborhoods, lining Benham Avenue and between Sixth and Main streets, were ready to boil.

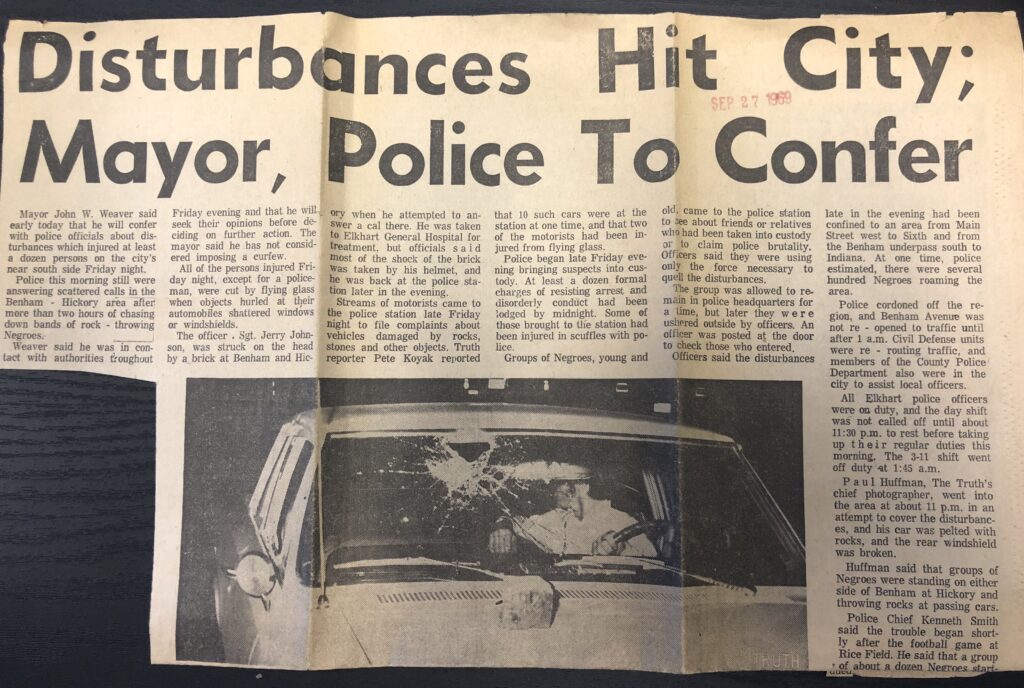

Blacks clashed with police the night of Friday, Sept. 26. A dozen people were injured by flying glass or hurled objects. Police K9 units were dispatched to break-up crowds, warning shots were fired into the air, and charges resulting from disorderly conduct and resisting arrest were in the works for dozens. As reported in the Truth, “Officers said they were using only the force necessary to quell the disturbances.”

Days later, it was reported no objects were thrown and no violence occurred until police dogs arrived on the scene.

At least 15 adults and six juveniles were arrested. As many as 50 cars were struck and damaged in the disturbances over the weekend, and police estimated the damage at more than $8,000. (The equivalent figure today would be in excess of $50,000.)

Conversations and concerns

While anger flashed in fiery words during the days and weeks following homecoming weekend, it was not coupled with hurled bricks or fired weapons. The pivotal moment was met with calm reason, from both city hall and the church pulpit.

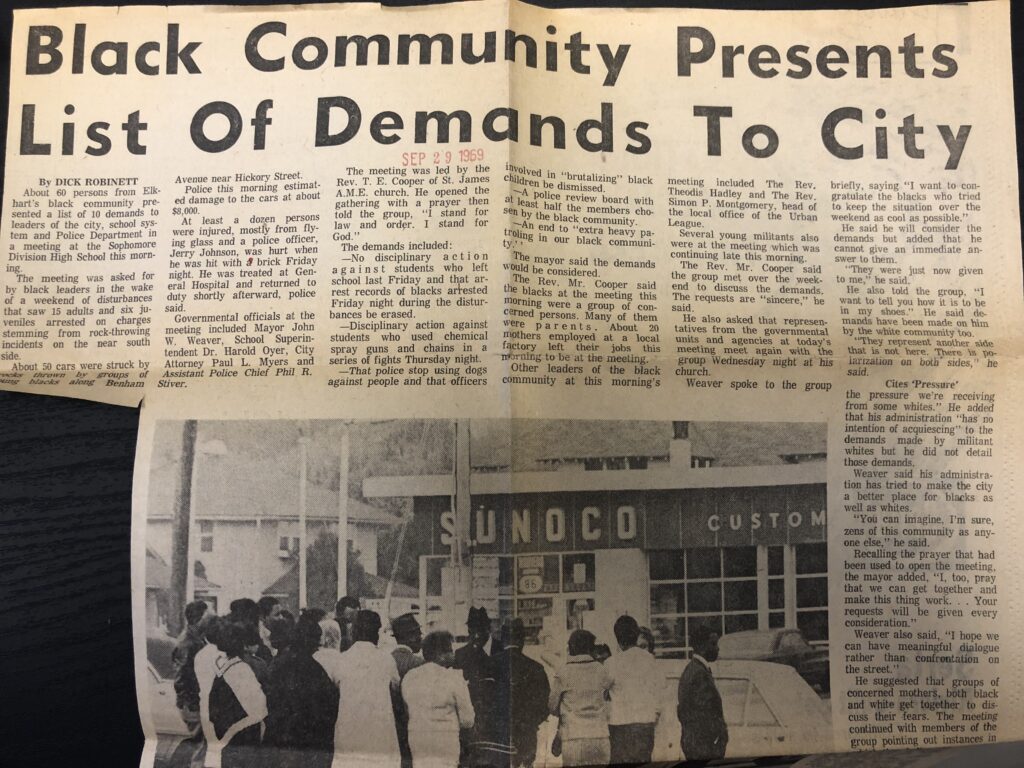

The Rev. Thomas Cooper of St. James AME Church and Mayor John Weaver were two of the voices restoring order in the community. Both men were present Monday morning, Sept. 29, when more than 60 people presented a list of demands. The meeting included 20 moms who left their factory jobs to attend.

The Concerned Citizens of the Black Community were beginning to be heard in Elkhart.

“(Weaver) told the group, ‘I want to tell you how it is to be in my shoes.’ He said demands have been made on him by the white community, too. ‘They represent another side that is not here. There is polarization on both sides. … I hope we can have meaningful dialogue rather than confrontation on the street,’” the mayor said, as reported by The Truth’s Dick Robinett.

The demands included:

• Stopping the use of police dogs as weapons against people;

• No charges for those engaged in civil disobedience;

• The creation of a police review board with equal black and white representation; and

• The ending of “extra heavy patrolling” on the southside.

About the same time, four Blacks were being held in contempt at city court and penalized $49 each for choosing to not stand when Judge John D. Shuman entered the courtroom.

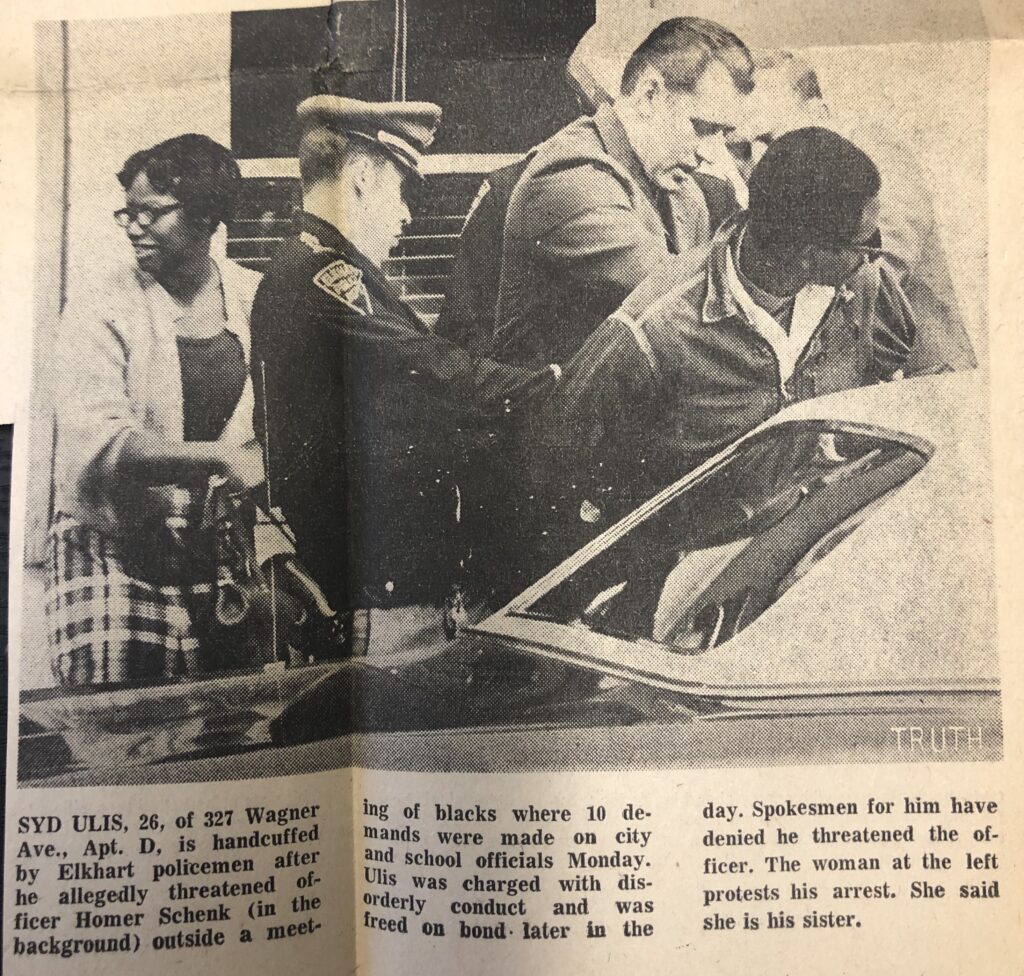

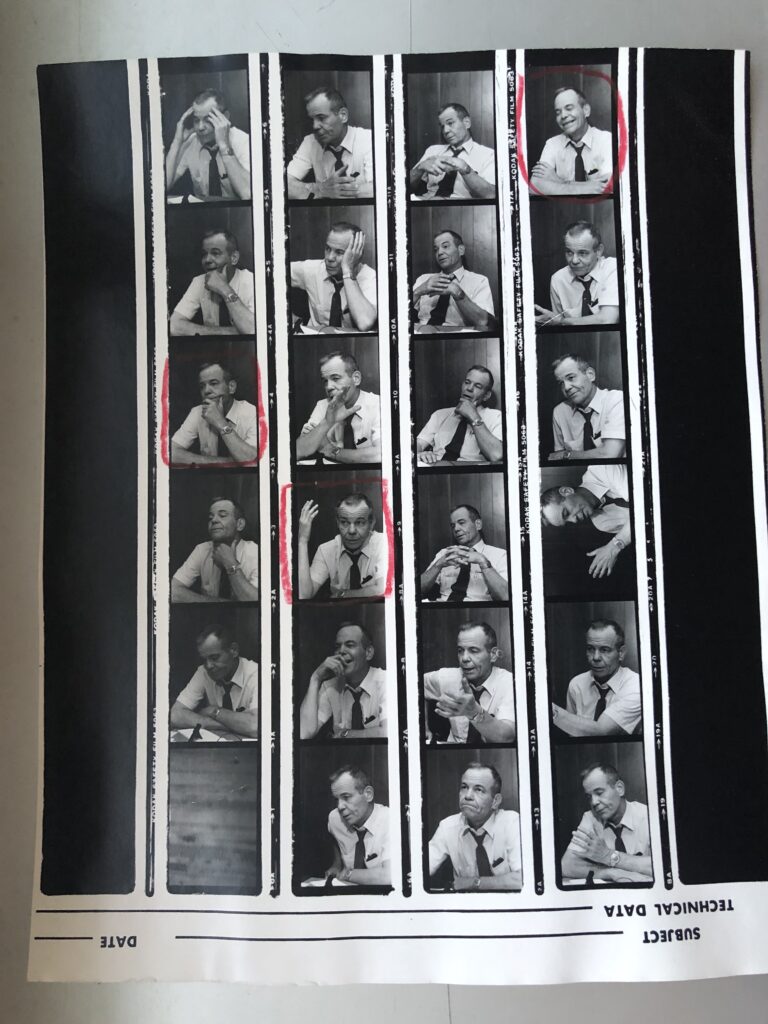

A second community meeting resulted in a calling out of the newspaper. “The Truth also was pointed out as ‘never taking pictures of peaceable meetings such as this but always reporting and using pictures when blacks were in trouble,” according to the Sept. 30 edition.

In sad irony, a three-column photo next to the same article showed a Black Elkhart man being handcuffed after he allegedly threatened an officer.

A glimmer of hope

To emphasize the fragile nature of the situation, The Truth quoted Rev. Cooper, “We have restrained the black militants to this point,” but the paper added, “he indicated that he is not certain how long this restraint could be effective.”

In the background, Cooper continued to work with groups like the Elkhart Urban League to conduct peaceful and productive conversations.

Arden Erickson, then The Truth’s city editor, wrote the Urban League convened black residents, white business owners, civic leaders “in an attempt to determine what really happened. The result of the session was some hope. Hope not only for a cooling of sentiments in the community, but hope also for a willingness on the part of all leaders and residents to seek solutions to long-standing problems of Elkhart’s black residents.”

Then, the legendary writer added, “While recognizing that no one person or group can speak for the black community no more so than one person can represent the white community, the Urban League and the blacks and whites there Tuesday night said they wanted peace. And more. Not simply peace for the sake of peace, but peace with the recognition that all is not good for the black resident in this community.”

Problems would not be solved overnight. Like the Urban League, Mayor Weaver also was asking for time. But inside City Hall, progress was happening.

Places far then near

At the start of a long, hot summer, The Elkhart Truth newsroom began collecting wire reports about riots and responses to racial issues from around the country.

The first newsprint clip saved in a repurposed envelope was from the July 28, 1967, edition of the paper. Under the headline, “A Presidential Plea – Restraint And Prayers,” the Associated Press covered the statements of President Lyndon B. Johnson on the growing discord in American cities.

In his remarks, LBJ “called for the long-range attack at every level on ignorance, discrimination, slums, poverty, disease and lack of jobs.” The words failed to soothe, and American cities were on fire throughout the summer.

Newark, N.J.

New Orleans.

Syracuse, N.Y.

Milwaukee.

Brooklyn.

Cincinnati.

Places far and near to Elkhart. Stories about attacks on police, discrimination on the basis of color, and marches to display civil disobedience.

In Detroit, United Press International reported statements by Michigan State Rep. David S. Holmes: “‘The community is like a dangerous sleeping giant right now and it could wake up and explode at any minute.’ He called for ‘disarming police and suggested they carry tear gas or other non-lethal weapons ‘as a first step toward building mutual confidence and respect between police and citizens.’”

Meanwhile, in Maryland, H. Rap Brown told his audience, “If this town don’t come around, this town should be burnt down.”

And closer still

By fall 1967, reports of demonstrations and disorder on all fronts were coming from Indiana cities.

Muncie South High School was the scene of 100 teens clashing in the main hall, the tensions heightened by the absence of any Black representation on the student council and in the honor society. A woman marching on City Hall in Evansville told an AP reporter, “Colored men are dying in Vietnam to keep white folks safe while I’m not safe on my front porch. That’s why I’m here.”

Baton Rouge, La.

San Francisco.

Harrisburg, Pa.

Des Moines, Iowa.

Kokomo and Fort Wayne.

Niles, Mich.

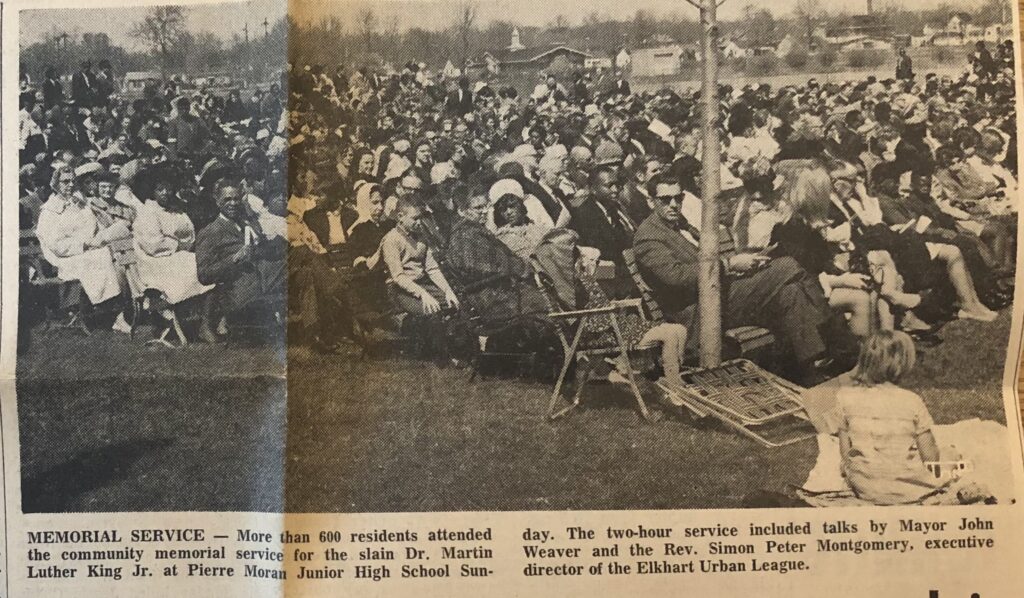

“Rioting, looting, burning and insurrection have nothing in common with civil rights,” The Truth printed in its April 9, 1968, editorial. “There is much to be done to improve America as a nation for all men regardless of color. … Certainly one of the first steps is understanding. But understanding can only come when the fear and fact of civil disorder by thugs and crooks is ended. This applies equally to white racists who would criminally assassinate Dr. Martin Luther King and to those black extremists who defy the law.”

Closer and closer. The envelope of yellowed newsprint was nearly full by Sept. 25, 1969, when the national clippings abruptly stopped. This now was becoming a news file on local events.

Time to speak out

As the community gathered and talked for one week, Mayor John Weaver listened.

Even as a group of 200-300 white residents began meeting to air largely ignored, opposing concerns, the mayor made only one position clear. In the Oct. 4 Truth, the mayor said, “The gap between community groups will have to be bridged through conversation.”

Weaver did not speak at length on the race concerns for another couple of days, nearly two full weeks after the Black high school students requested representation in homecoming festivities.

“The leaders and members of this committee have, I believe, dealt with us in good faith and I commend their sincerity and concern,” Weaver said Oct. 6. “This committee has suddenly and clearly made this community aware of various real problems that can no longer be ignored and which all people of good faith in this community must get together and solve now.”

The mayor said the southside patrols were justly criticized by the Black community, and changes would happen immediately. He announced the police chief must make his K9 policy known. He said a police conduct review board was not possible under law, but “constructive criticism” was welcome to be shared at regular safety board meetings.

Under the headline, “Weaver’s Answer Takes Path Of Middle Ground,” Robinett wrote about one other aspect of the mayor’s statement.

Beyond the government’s actions, Weaver was critical of parents and the communications they were having with their children. He called on parents to be more active participants, including even sharing rides with police officers and addressing problems before the authorities needed to get involved.

The statement resolved immediate tensions. No charges were pursued against those arrested.

‘smile on your brother’

Disturbances would continue, including several days of action after a scuffle involving 100 students at Pierre Moran Junior High in October 1970.

For the most part, though, a lasting imprint of Homecoming 1969 was the need for more communication and understanding between all members of the community.

By Oct. 10, the headlines of The Elkhart Truth returned to coverage of Vietnam War protests, the fate of the County Home, and the building of a new school campus and Career Center on the city’s west side.

The truly memorable words about the events which began to boil Sept. 24, 1969, were written by the yearbook staff of the Blazer Pennant.

The usually light-hearted memory book presented a sobering summary in the opening pages of its 1970 edition. Written in startlingly bright, lowercase script on black pages are these words:

“tensions of a long ignored problem exploded on the scene at ehs in the fall. the racial tension during football homecoming polarized the student body, sharply limited school activities for the remainder of the year and affected everyone in some way. …

“ideas are not black/white. in our classes we agreed or disagreed, listened attentively or just slept, saw with startling clarity how all of it fit together, or despaired that nothing would work out.

“sometimes we just laughed.

“ironically the tension and conflict came when we tried to pull together in school spirit at homecoming. yet, it was in our daily living and fun that we came to share the most with each other. and the beat goes on …

“life in its own way is a miraculous teacher. it teaches us that problems which are ignored can never be solved.

“come on people smile on your brother … let’s do it together”

Lasting impressions

Rev. Cooper continued to provide leadership in building community consensus and understanding into the early 1970s. He also served on the board of directors for the Elkhart County Association for Mental Health. He left St. James AME sometime in 1973, a transfer ending seven years of service locally.

“We are working toward reconciliation and unity without placing blame on anyone,” he said in an April 18, 1970, Truth report after several nights of minor disturbances in southside neighborhoods.

Parents and youth came together to air concerns at local churches and with parent-teacher associations. Two human relations clubs formed at the high school, allowing students to spend more time communicating on race issues. The school newspaper became an open forum for sharing different views.

The Police Community Relations Group, a product of Mayor Weaver’s announcements following the Elkhart High issues, brought together 39 people from various walks of life and established a number of youth clubs and activities throughout the city, according to a feature article Nov. 3, 1970.

Mothers, too, were getting together to discuss common challenges. On April 21, 1970, Truth reporter Nancy Hulvershorn documented the “Being a Woman in Today’s World” event at Oaklawn Center.

“‘In today’s world, where we have instant everything, space exploration and a global village, the job of a mother seems almost insurmountable. But like yesterday, children still come to us for love, comfort and understanding,’” Mrs. Redgie Weissert told the room of 160 women that day. Hulvershorn also reported, “Mrs. Weissert said that teen-agers are more interested in politics than many of their parents are or ever were.”

More discussions were needed, but leadership throughout the community was changing.

A time of change

By March 1972, Superintendent Oyer left Elkhart to run the public school district in suburban Pittsburgh. In an article reflecting on his work locally, Oyer told The Truth, “We’re going to have to learn to live with each other. The more you talk to people, the more you realize there is almost unbelievable misunderstanding of the racial problems.”

Mayor Weaver chose not to seek a third term in 1971. His eventual return to politics resulted in one of the closest races in Elkhart history, a 58-vote loss in November 1983 to Democrat James Perron. Shockingly, just four years later, Weaver died of a heart attack at age 59.

The Elkhart Truth editorial board fondly remembered Weaver’s contributions in a July 5, 1987, tribute.

“Let it be said here that Mayor Weaver held the community together in a much more meaningful way than with bricks and mortar. Note that he was mayor in the turbulent ‘60s. Nasty racial flareups were common in Indiana cities. Though on the brink many times, Elkhart escaped a major outbreak of violence.

“Jack Weaver was not a hand-wringer nor did he stick his head in the sand. He confronted and challenged both blacks and whites who would incite to riot. His was quiet leadership, one on one often, with citizens whose passions had overcome reason.”