A dark winter filled with anguish, uncertainty … and hope

At Christmastime in the midst of a different dark winter, Elkhart already had lost far too many souls.

The weather was unseasonably warm. Main Street had no snow, but it did have a mobile Marine Corps recruiting station. Stores like Berman’s and Ziesel’s and Rosen Brothers ran festive holiday ads in the newspaper. The other pages were darkened with grim reports from across two seas.

And speaking of the paper, sales of The Elkhart Truth were breaking records – all the more eyes to see the needs of the Red Cross and read about the anguish of the families waiting to hear from their boys stationed in the Pacific.

Routine life was upended. The promise of the future was unknown. These were the days immediately after Pearl Harbor.

“Say now finale and farewell to the old world you would have known, to the ways of peace, of idleness, of luxury,” The Truth editorial proclaimed on Dec. 12, 1941, near the end of that anguished week. “Say goodbye now to a world in which the powers of darkness creep … over the lands of free men.

“Hail the new world that shall be built on the ruins of the old one – a new world in which justice shall rule, and men shall be free from tyrants. … The past is a bucket of ashes. Here’s to today – and the clean, brave, free tomorrow for which we fight – tomorrow is an America worth fighting for!”

The patriotic and generally positive nature of the editorials displayed a brave face. The leadership of The Elkhart Truth, as was the case with every business, dealt with challenging conditions while the country around them powered up for war.

A changing workplace

Inside a black three-ring binder are neatly kept, typewritten company memos from The Truth, circa 1930-43. The likely forgotten piece of history was located among newspaper clips and photos as Elkhart Public Library staff started working with The Truth’s historical archive.

Bettie East’s name and home address appear on the front of the binder. How she came to possess the early memos before she started working for The Truth is unknown. What she must have thought of a particular December 1941 memo can only be guessed.

Bettie Lines – as she was known then – had just “convinced city editor Emerson ‘Abe’ Martin that it was time to give her a chance at reporting” as World War II approached, according to an 1987 article by Arden Erickson. “(Martin) promised her there would be ‘no special favors’ just because she was a woman, and turned her over” to work with a more seasoned reporter.

She certainly wasn’t the first woman in her profession, but a trailblazer nonetheless – her career spanned nearly 50 years. During the war, she was given the difficult task of interviewing families of soldiers killed in action. She also saw first-hand the many faces heading out from their Hoosier hometown to fight the good fight.

“The Elkhart girl knew a lot of the boys who were drafted during the war, and gave a good number a proper send-off when they were inducted. The boys would assemble at the Western Union office … and it was Lines’ job to write down their names (for the paper). ‘There were always guys that I knew from high school, and I kissed them goodby,’” Erickson quoted East as saying.

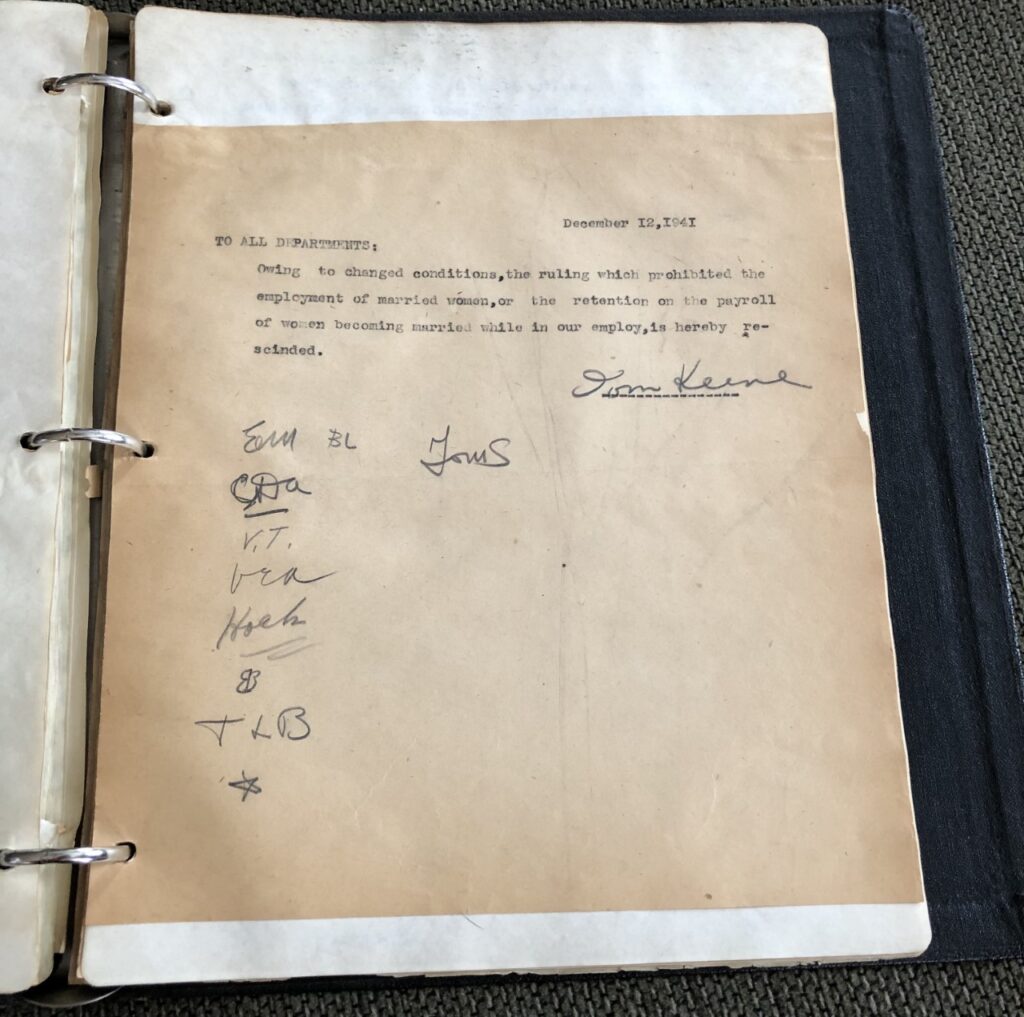

Luckily for the newspaper and the community, Lines was still single and could work. Until Dec. 12, 1941, The Truth had certain rules.

“TO ALL DEPARTMENTS:” started the memo that day from editor Tom Keene, “Owing to changed conditions, the ruling which prohibited the employment of married women, or the retention on payroll of women becoming married while in our employ, is hereby rescinded.”

Business practices were changing rapidly.

‘All these must be kept up’

The company memos cover all the usual, mundane newsroom topics – style points, late press start times, long distance phone calls, and numerous reminders to stay accurate. By October 1941, though, memos addressed the war drums starting to rumble.

“Because of the real shortage of … paper and other allied products, the government is preparing to use newsprint in quite large quantities for wrapping purposes,” editor Keene wrote to all departments Oct. 24, 1941, under the heading of “protecting our own sources of supply. … We shall be serving our own interests if we promote conservation of all forms of paper materials, and urge the preservation of scrap paper upon any and all occasions.”

Sometime between Oct. 29 and Nov. 11, as the memos are kept chronologically, Keene expanded the conservation efforts to include “waste paper, paper towels, water, light, typewriters, machines, soap, paper clips and rubber bands – anything and everything we use in the office and plant, wherever it can be done. …

“During this grave emergency, and for the duration, we shall be obliged to save everything we can, wherever we can. By effecting such savings, we shall be serving the interests of both Uncle Sam and ourselves.”

Within 72 hours of the strike on Pearl Harbor, a small item on the front page announced the U.S. would “Ban Tire Sales Until Dec. 22” so the government could develop a plan for controlling rubber distribution. Many everyday goods eventually would be rationed, and some simply were unavailable.

One such product impacting The Truth’s business was the typewriter; by the summer of 1942, none were being manufactured. “Therefore, it behooves each of us to keep our machines clean and well oiled, lest one day we find ourselves obliged to resort to pencil pushing,” Keene wrote.

On the editorial pages, the newspaper struck an upbeat and encouraging tone about all the hasty shifting.

“The ordinary routine life of America must go on,” according to the Dec. 18 opinion under the headline “How Can I Help?” “The wheels of industry and commerce, of education, of religious training, of business and of the professions, the intensely important task of maintaining house life and preserving the well being and the morals and the health of the younger generation – all these must be kept up. It is for these – for the stability of living in the American way – that we as a nation fight.”

Everyone was making small sacrifices, but some were suffering the greatest loss of all.

An unsettling silence

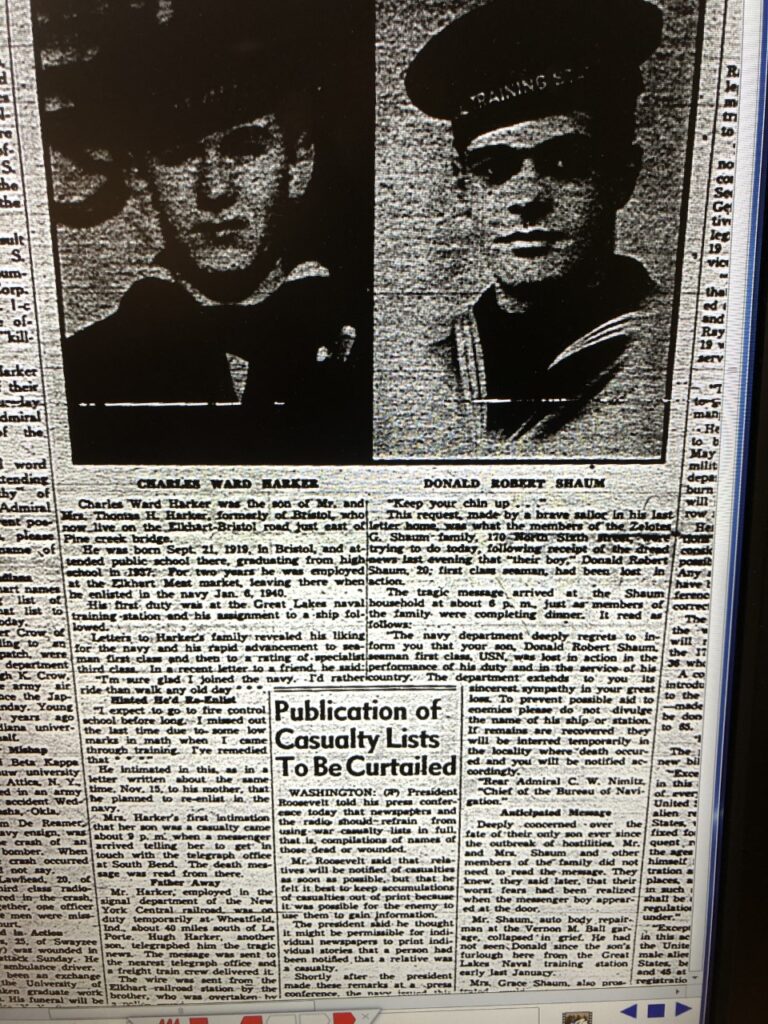

Elkhart grieved the loss of four local men killed at Pearl Harbor. One of the first stories to be shared was about Pvt. Robert Lee Schott. His parents told a Truth reporter the “news of his death arrived just two days after they had received a Christmas package from him” and they, in turn, were preparing to wrap a sweater to ship to him.

Paragraph after paragraph in the Dec. 8, 1941, edition of The Truth listed the last known whereabouts of soldiers and others known to be in Hawaii, on ships at sea, or in other Pacific locales.

Merril Koebernik, third class radio man on the U.S.S. Minnesota, was due to have his enlistment expire in December 1941, but told his parents in a letter written Nov. 16 “he didn’t expect to be released until the fleet got back to the mainland.”

The mother of Private Eugene Achburger, a mechanic with the 42nd Bomb Squad on Hickam Field in Hawaii, “heard from him two weeks ago, at which time he was waiting his turn as a pilot.”

About Private William Baker, first class fireman on the U.S. mine sweeper Harrison, “Mrs. Robinson received word from her son Wednesday that his ship would be in port several months for overhauling.”

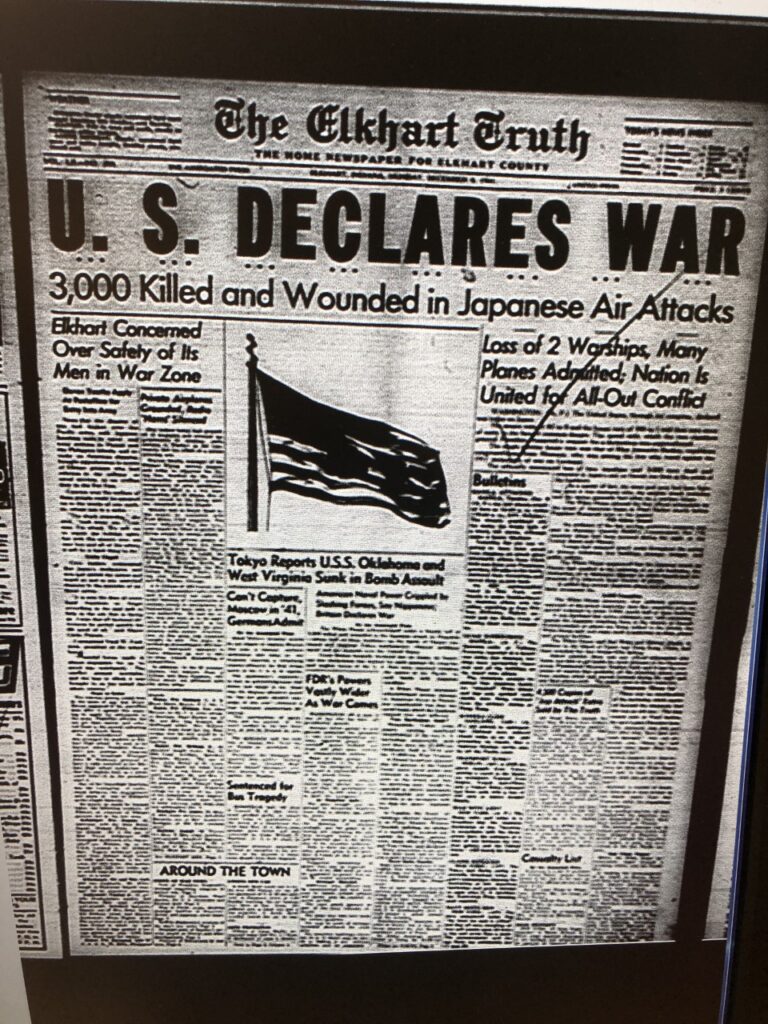

These details and many, many more filled pages under the massive triple-decker headline:

U.S. DECLARES WAR

3,000 Killed and Wounded in Japanese Air Attacks

Elkhart Concerned Over Safety of Its Men in War Zone

Soon, the newspaper could not supply such detailed information about those abroad, adding unsettling silence to the dark winter.

“STAFF MEMO: To comply with a war department memo to the press, we will no longer designate the organization or location of service men who are outside the continental limits of the United States,” wrote city editor Abe Martin on Dec. 10. “We will, however, continue to give their organizations and stations if they are within the United States.”

During this time of war, the newspaper did not choose to fight its government on First Amendment grounds.

“President Roosevelt has asked that accumulated totals of American casualties be kept out of the newspapers, because of the value which the information might have to the enemy,” read the editorial, “Gold Stars Again,” on Dec. 13. “However, every Elkhartan who has read The Truth for the past week knows the number of Elkhart men who have so far laid down their lives for their country.

“Naturally the thought arises that if other communities have suffered losses in proportion, the nation’s casualties to date must be extremely heavy. There is no reason to conclude, however, that this is the case. The long arm of coincidence may have reached out and touched us. …

“Until the curtain which necessarily has been lowered over the extent of our losses is lifted, we can but hope that the blow the entire country has suffered is not in proportion to that dealt Elkhart in the opening days of the Second World war.”

Still a season to give

Elkhart residents answered the call in many ways after Pearl Harbor. The Truth reported the Army recruiting office in South Bend was swamped by local boys wanting to enlist, and 43 were set to enter the service by year’s end.

The American Legion put donation boxes by store cash registers for “Smokes and Candy To Be Sent Elkhart Men in Service,” according to the Dec. 14 headline. Teachers were preparing to learn civil defense drills to instruct children, and the Red Cross organized sewing and knitting groups to craft clothing, scarves and snow suits.

A Christmas Eve headline proudly announced “City Pours Over Million Into Defense” with residents purchasing war bonds and stamps from banks, stores, and Truth newspaper carriers.

“It is true that the usual words of greeting and good wishes, voiced at the holiday time, sound hollow now,” the Dec. 19 editorial read, “in a day when there is no peace on earth, and bet little merriment in any land. … War this year, to be sure, casts its dark shadow over the Christmas lights. But it must not dim our courage, nor shake our confidence.”

More than 220 Americans would die, on average, each day during World War II. Elkhart County cast 270 names in bronze on the War Memorial in front of Goshen’s courthouse, remembering those who perished in the four-year fight.

On Dec. 24, the editorial offered, “It was the Christmas when there was always a little group of grim-faced people reading the war bulletins in the Truth office window … when people wondered in dread and foreboding what day the next casualty lists would be posted … when many young men seriously intent on their holiday pleasures wondered where they’d be this time next year.

“But still it was Christmas. And still the people of Elkhart strung colored lights on the trees in their dooryards … and sang the old carols … and hung wreaths in their windows … and gave gifts to each other … and gathered their families together again in their houses … and even as they steeled their minds for war, bowed their heads at the Crib of Him who gave them the vision and the promise of peace on earth … for men of good will … and stout hearts.”

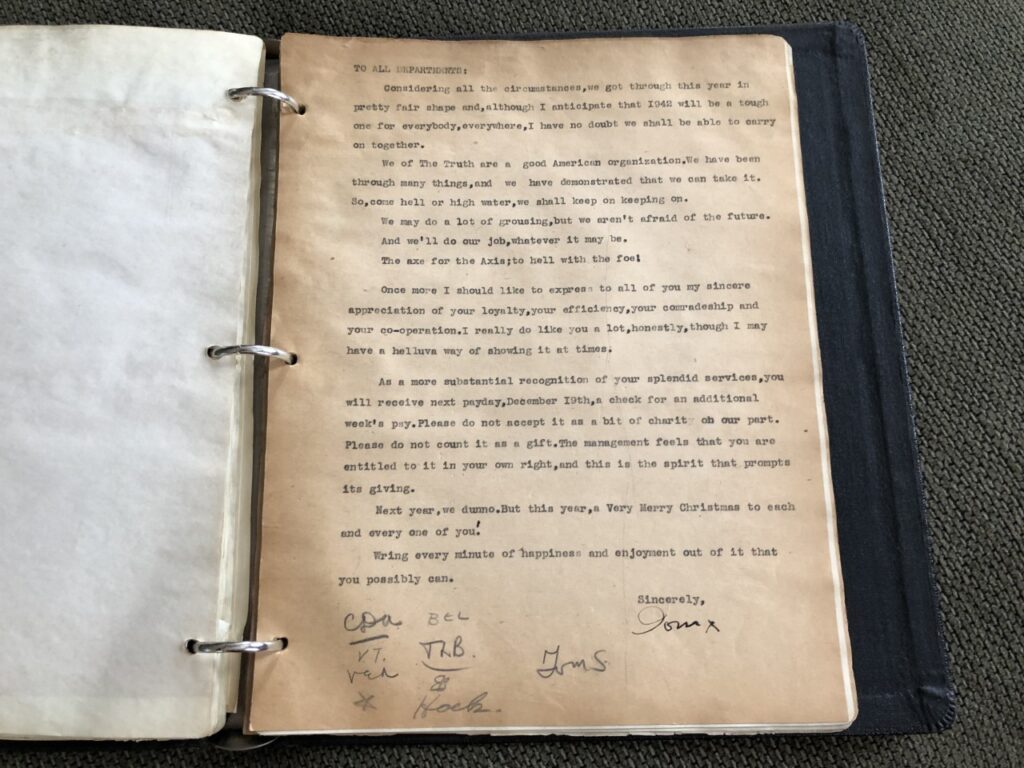

As the emotional weeks of December drew to a close, editor Tom Keene – celebrated for his journalistic accomplishments, including his poignant holiday letters – sent a page-long memo to the staff.

“TO ALL DEPARTMENTS:

“Considering all the circumstances, we got through this year in pretty fair shape and, although I anticipate that 1942 will be a tough one for everybody, everywhere, I have no doubt we shall be able to carry on together.

“We of The Truth are a good American organization. We have been through many things, and we have demonstrated that we can take it. So, come hell or high water, we shall keep on keeping on.

“We may do a lot of grousing, but we aren’t afraid of the future.

“And we’ll do our job, whatever it may be.

“The axe for the Axis; to hell with the foe!

“Once more, I should like to express to all of you my sincere appreciation of your loyalty, your efficiency, your comradeship and your co-operation. I really do like you a lot, honestly, though I may have a helluva way of showing it at times. …

“Very Merry Christmas to each and every one of you! Wring every minute of happiness and enjoyment out of it that you possibly can.”