Al and Helen Free understood science and changed the world

Retired from Miles Laboratories for more than a decade, renowned scientist Helen Free kept incredibly engaged in her work.

From serving as president of the American Chemical Society to nurturing Elkhart’s young students, Free kept a fast pace in 1993. She was even too busy to accept a YWCA Woman of the Year award in person.

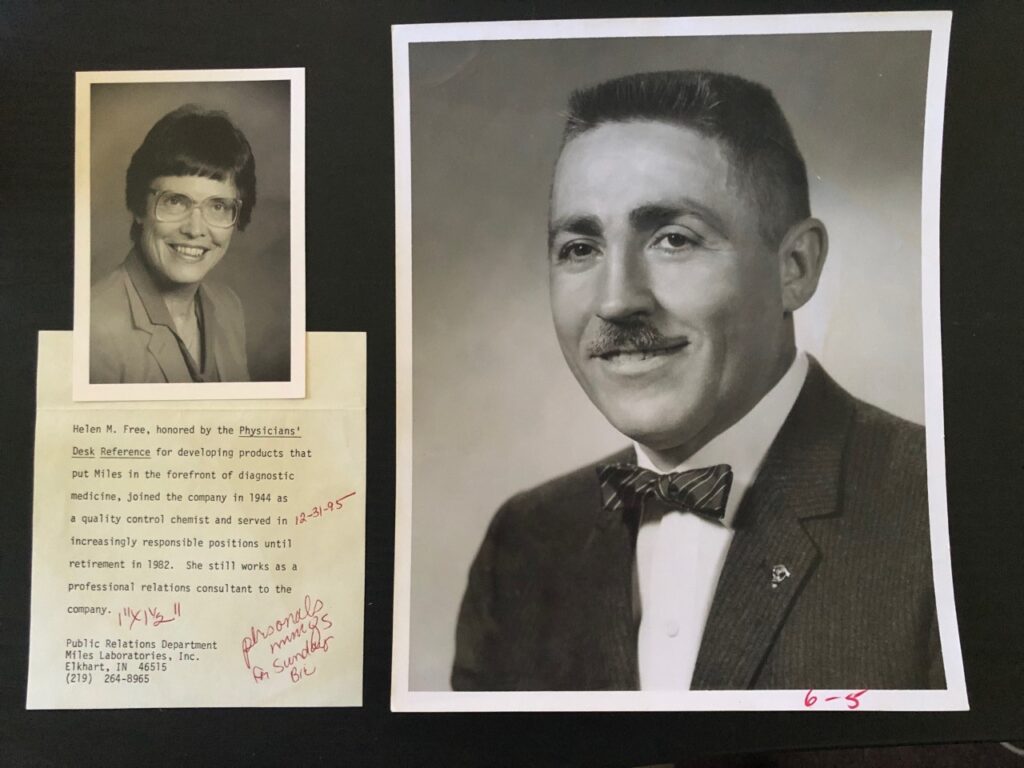

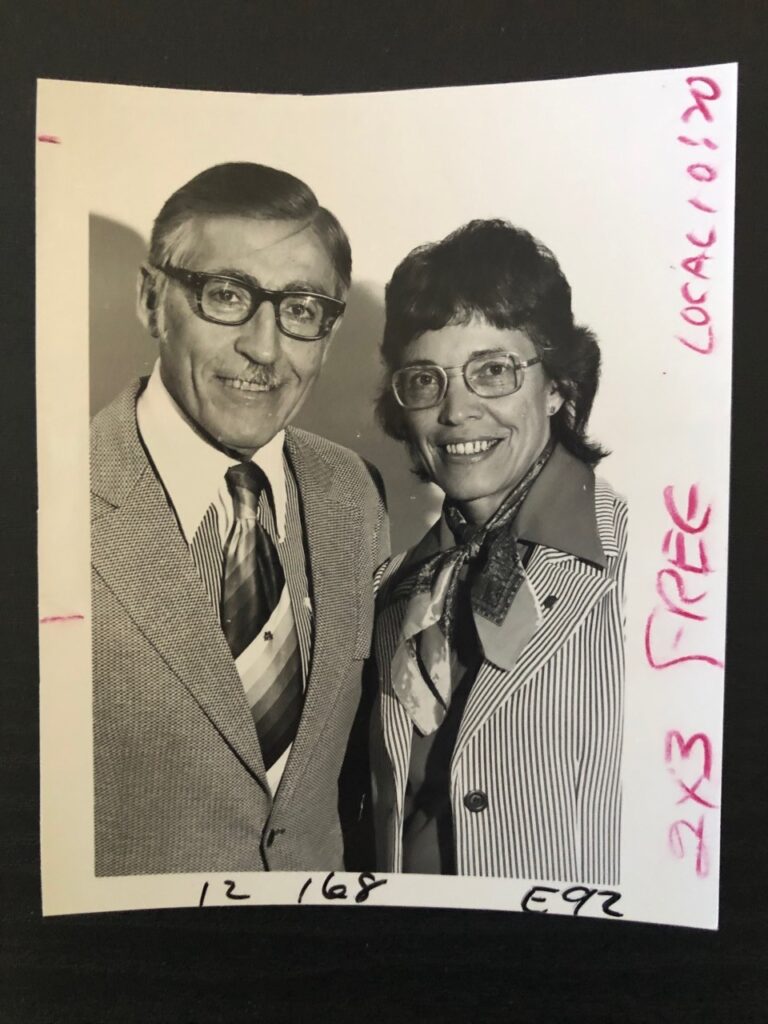

Helen Murray Free was exceptionally talented. Her husband, Dr. Alfred Free, was her equal in the profession and in the house.

They changed the world from Elkhart with their research, including the creation of diagnostic tests improving clinical laboratory procedures and, eventually, home self-tests.

They raised nine children in a growing home on East Jackson Boulevard. Their shared passion for chemistry kept going long after their official careers at Miles Laboratories came to an end. And they still found time in their busy schedules to contribute to the betterment of the Elkhart community.

Vast opportunities

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Helen Murray’s mother predicted vast opportunities for women in the field of science with men going off to war. The conversation between the two resulted in a new career path for Helen – who may have otherwise ended up a teacher – when she earned her degree from the College of Wooster in 1945.

Alfred took his doctorate in 1939 from Case Western Reserve University and was already in the field when the United States entered the war. Upon their joint induction into the Engineering and Science Hall of Fame in 1996, among Al’s accomplishments listed was his groundbreaking research to determine the efficacy of oral penicillin as an aid to ailing soldiers.

Upon arriving in Elkhart to work for a division of Miles Laboratories, the research and innovations of both scientists continued to draw notice. They wrote more than 150 technical papers and two books, took more than dozen patents for intellectual property, and introduced countless ideas to improve clinical lab procedures with dip-and-read reagent strips for blood and urine.

She received credit for her leadership in the testing of newborns for genetic and metabolic disorders, including those considered as potential early indicators of cognitive development issues. In 2009, she received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation from President Barack Obama.

At Miles Laboratories, Helen Free held management positions in research, product development, and technical services. Al Free served as technical services director at Miles, earning honors along the way from the American Institute of Chemists and the American Association for Clinical Chemistry.

“His concept teaching has inspired thousands of scientists all over the world,” Robert Ondohl, regional vice president of Fisher Scientific Co., said in a 1982 Truth report.

A well-researched home

At home, Al and Helen Free discovered the science of fitting a large family into what was once a small riverside home at 3764 E. Jackson Blvd. In November 1966, The Truth’s Janet Cox took readers on a visit to the Free home, which was just four rooms 20 years before when they moved in.

“(E)xpanded and remodeled into a spacious and comfortable home that accommodates all the varied activities of a large and busy family with ease,” Cook wrote. The decorations were informed by Al’s research of contemporary home magazines, but Helen “chose the hanging light fixtures because the globes remind her of some of the flasks used in the laboratory.”

They had to purchase the lot next to theirs for the biggest expansion, taking the house to 11 rooms total, with two complete kitchens, four baths, and an Indiana limestone fireplace. With six kids ranging in age from 3½ to 17, the floor plan included plenty of space for a wide-range of activities.

“For the more adventuresome a skateboard ramp built, by Eric and his father, provides a thrilling splash in the river,” Cook wrote.

Working retirements

When the company retired Al in 1978 – “without my concurrence,” he told Truth reporter Jim Miller in November 1991 – the work did not stop. Helen also stayed at it after her retirement date in 1983, and both kept work offices at Miles Laboratories as consultants.

Al turned some of his attention to the greater concerns about the fields of science and education. By the early 1990s, he observed a decrease in the number of students studying chemistry and earning advanced degrees. The shortage would set the United States behind the world if it continued.

“If the situation does not reverse itself, there will be (a) shortage of American chemists in the next 10 to 12 years,” Free told The Truth. “U.S. companies needing chemists will be forced to import them. … Chemistry is such an important component of our whole industrial concept, there’s a real threat of becoming a second-class nation.”

At the time, Miles employed more than 100 chemists in the Elkhart-Mishawaka area. When Miles was acquired by Bayer and eventually relocated, the Frees saw change was coming. They were working to make sure science did not leave the area along with the jobs.

“Kids when they’re in the early grades in school have an intense interest in science. They’re interested in how things work,” Al told The Truth’s Miller. “Having a supply of chemists is a fantastically important thing. You have to get people at a young age” and put them on the career path before other occupations compete for attention.

Helen Free equally was moved to make a difference in the next generation. In a March 1993 article, reporter Terry T. Mark wrote, “One of (Helen’s) crusades now is to get more children interested in science.” She mentioned specifically a twice-monthly newspaper column published through USA Today to promote interesting stories for youth and adults.

Together, during summers, they brought second and third graders together for “Science is Fun” classes.

True vision and service

A decade after leaving full-time work at Miles Laboratories, Helen Free – at the age of 70 – became president of the 145,000-member American Chemical Society.

When the St. Joseph County YWCA moved to honor her election and lifelong accomplishments, she couldn’t attend the spring 1993 ceremony. She was moderating a worldwide teleconference for the society, along with preparing for an educational trip to China on behalf of her former employer.

“A lot of teaching and workshops for technical audiences,” is how she described her days in March 1993. “I was lucky because I could have all these different kinds of careers. Miles has been a great influence.”

Their service to local causes was notable, as well.

In 1983, Al was recognized as the Elkhart Lions Club Citizen of the Year. He served as the group’s president in 1960-61 and started the club’s eye bank committee, which later became a statewide initiative. He also helped form the Cystic Fibrosis Society of Elkhart.

Helen gave her time to the Elks Ladies, Elkhart Concert Club, the Elkhart Centennial Committee, the YMCA board of directors, and First Presbyterian Church, along with organizations like the American Association of University Women and United Fund.

Alfred Free, 87, passed away on May 15, 2000. Helen Murray Free, a frequent guest at the Dunlap branch at Elkhart Public Library through the years, died May 1, 2021, at the age of 98.