The best newspaperman Ernie Pyle ever knew called Elkhart home

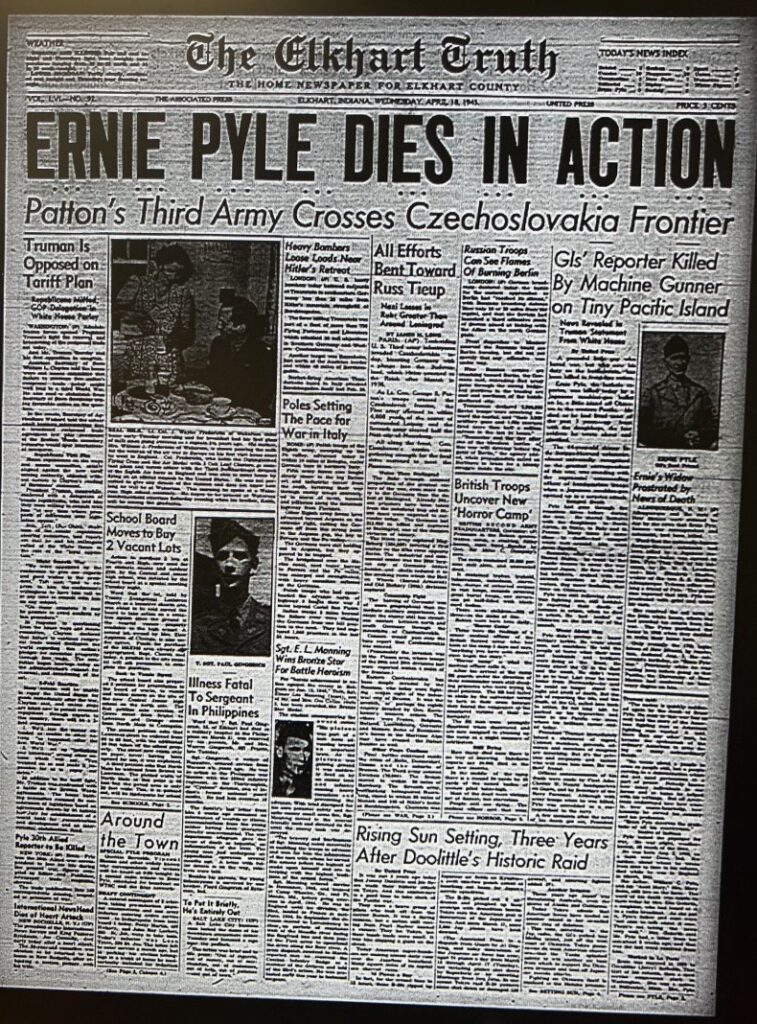

During the final cruel days of World War II, the last of Ernie Pyle’s war stories was published with an editor’s note in The Elkhart Truth.

Pyle, the famed newsman, met his end in a ditch on Ie Shima island – felled when a sniper’s bullet struck him in the head. The nation would grieve for someone who was always welcome in their homes, even if they’d never met face to face.

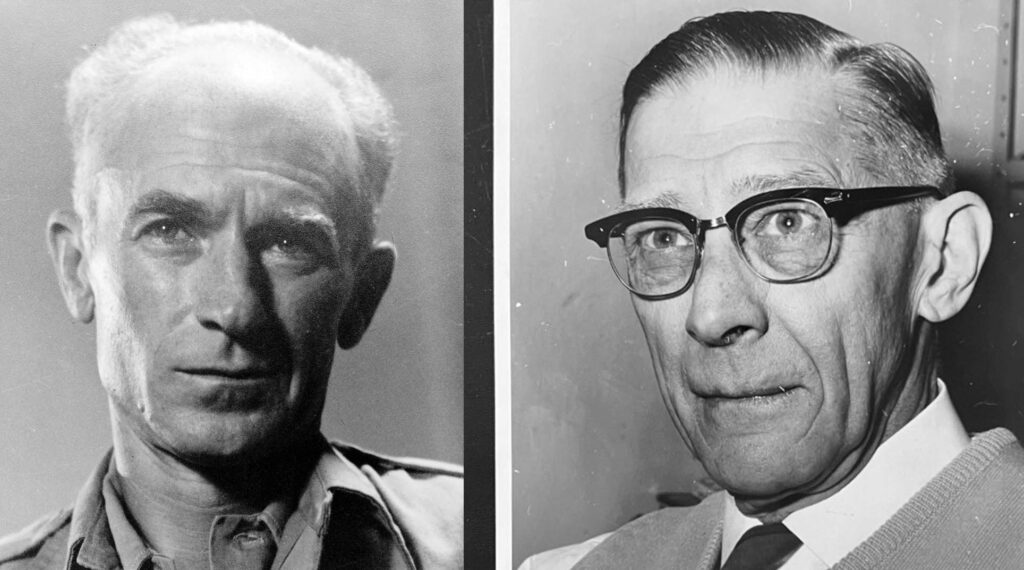

To Emerson “Abe” Martin, The Truth’s news editor, the loss was deeply personal.

Pyle and Martin were roommates working at an upstart D.C. paper in the 1920s and were pen pals for at least a few years. With time and distance, the friendship may have lapsed. The mutual admiration, though, remained strong.

Martin was professional, stern and no-nonsense. He likely showed no emotion to his coworkers when the tragic news came across the wire on April 18, 1945. The editor’s note, though, shared his deep affection for Pyle, whether or not he wrote this unsigned copy:

“In addition to the story which appears here today, we will print several others which we have received from Ernie Pyle in Okinawa. We believe he would have wanted us to,” the note read. “As a great reporter, a great newspaperman and a great person, he would have wanted his stories to go through, despite his tragic death.”

‘My spirit is wobbly’

April 1945 was particularly tough for all Americans. The war in Europe was nearing its brutal end, with both fronts closing in on Berlin. The atrocities at concentration camps were coming into full view. Allies were progressing island by island through fierce fighting in the Pacific. President Franklin Roosevelt died at Warm Springs.

And then Ernie Pyle, the Hoosier Vagabond, every soldier’s best friend … gone too soon.

President Harry Truman, just a week on the job, took to the radio airwaves to break the news himself. One newspaper editorial pointed out there was no vice president to take Ernie Pyle’s place.

Just months before his death, he witnessed the Allies storm into France on D-Day. Pyle was ready to be done with working from the war zone.

“I’m leaving not because of a whim, or even especially because I’m homesick,” Pyle said of returning stateside. “My spirit is wobbly and my mind is confused. All of a sudden it seemed to me if I heard one more shot or saw one more dead man, I would go off my nut.”

He felt obligated to tell the stories of the troops, though. He ended his short stay at home to travel the Pacific. Thousands of miles away, Abe Martin knew why.

Ernie Pyle’s perfect job

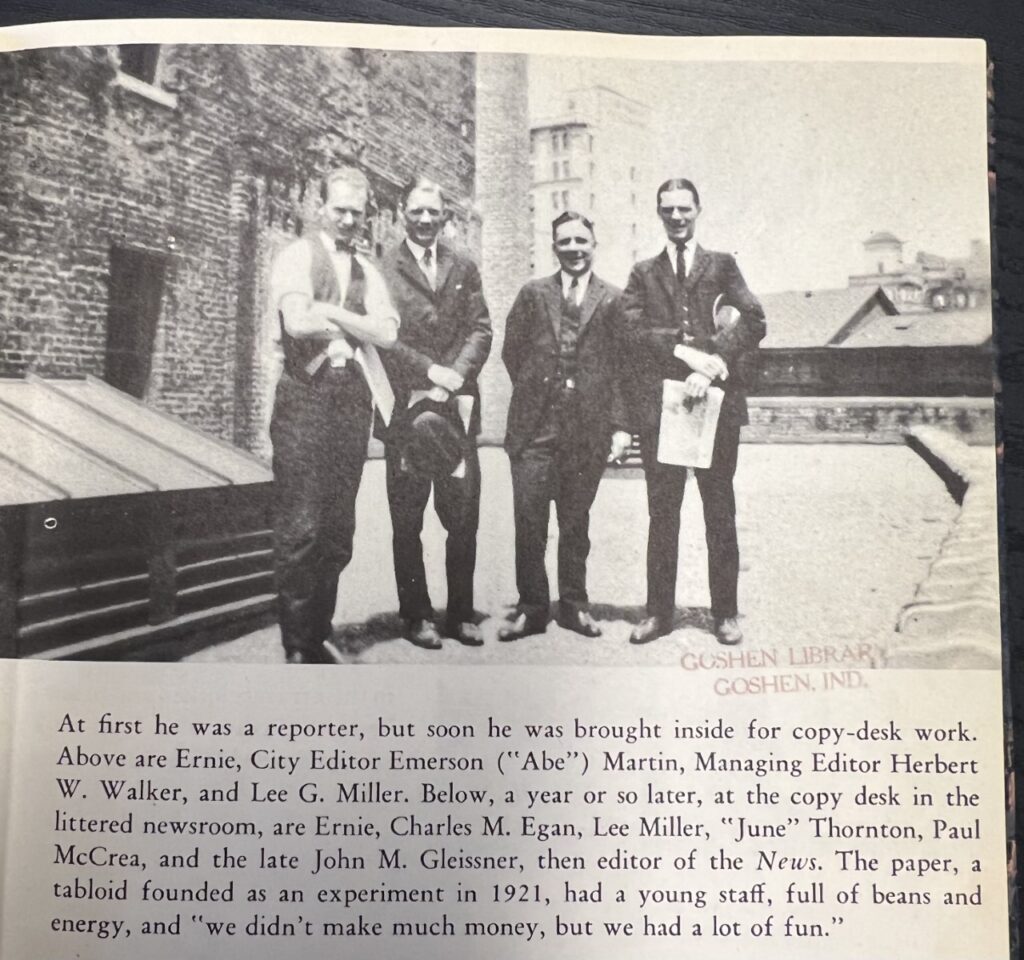

In 1943, in perhaps the only words put into print about his friend, Martin wrote, “It was during an evening bull session, while Ernie Pyle was a very young reporter on the then very young Washington Daily News … that he said: ‘You know, my idea of a good newspaper job would be just to travel around wherever you’d want to without any assignment except to write a story every day about what you’d seen.’ …

“That’s what Ernie finally got to do.”

Martin and Pyle were different in that way.

Raised in Elkhart, Abe was destined to return home after his short assignment in Washington. He married his sweetheart, Margaret “Peg” Burns, and started a family in his hometown.

After 15 years of marriage, Ernie eventually settled in New Mexico with his wife. But that was just before the start of World War II, and his spirit was always roaming.

“Glad you have a nice house in such an ideal location, and hope you are satisfied and thoroly happy,” Pyle wrote to Martin in a personal letter postmarked Feb. 9, 1925. “I am not, but of course I am the kind that never will be and wouldn’t be happy if I was.”

Words that matter

“Whether he knew it or not, (Pyle) had the gift of writing things the way they are apt to be said,” Martin wrote in The Truth in 1943. “So, there would be little unconscious errors in grammar, just as there are in his columns today. They didn’t get by then; today they can be recognized as part of his distinctive style.

“One day, in a story about a starveling kitten that had been fed by some kind person, Ernie said the kitten was ‘completely serensified.’ There’s no such word; but the context and the word made Ernie’s meaning clearer than any proper dictionary word could have done.”

Ernie Pyle’s syndicated columns appeared in hundreds of daily papers and were read by millions. His vivid storytelling in casual and compelling voice was can’t-miss reading. He told the frontline story and ignored the strategy of warfare.

“You feel small in the presence of dead men, and you don’t ask silly questions,” Pyle wrote.

In a 1995 Associated Press tribute, biographer David Nichols said Pyle “was the reporter he was because he really didn’t give a damn about the news.”

‘Big league stuff’

“(Pyle) was 42 years old, a balding hypochondriac who was twice the age of most soldiers,” the Associated Press columnist wrote in his tribute. “Rail thin, friendly, profane, he rolled his own Bull Durham cigarettes and liked to carouse with colleagues. He was the disheveled guy in the knit cap.

“… Pyle wrote unashamedly of American troops’ ‘fighting spirit.’ But he also described their dark humor, misery, boredom and homesickness, and the terrors they endured.”

Martin, in 1943, told Truth readers Pyle picked up “the itch” during World War I, sweeping the North Sea for German mines on duty with the U.S. Navy. From Indiana University and later newspaper assignments, he traveled far and wide and perfected his storytelling. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his correspondent work.

“It was during the London blitz that it became big league stuff,” Martin wrote. “Because Ernie was doing just what he’d always done – writing common little things about common little people in just about the clearest composition that ever graced a newspaper column. … He was never one to spend half a dozen words on an idea when one little active verb would handle it.”

Letters between friends

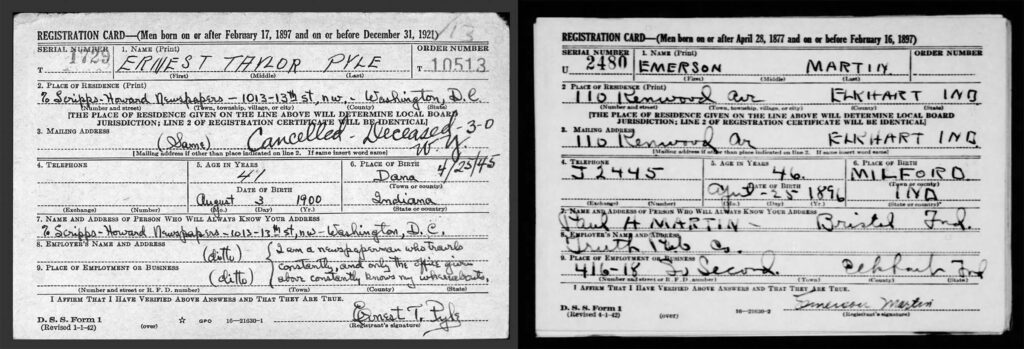

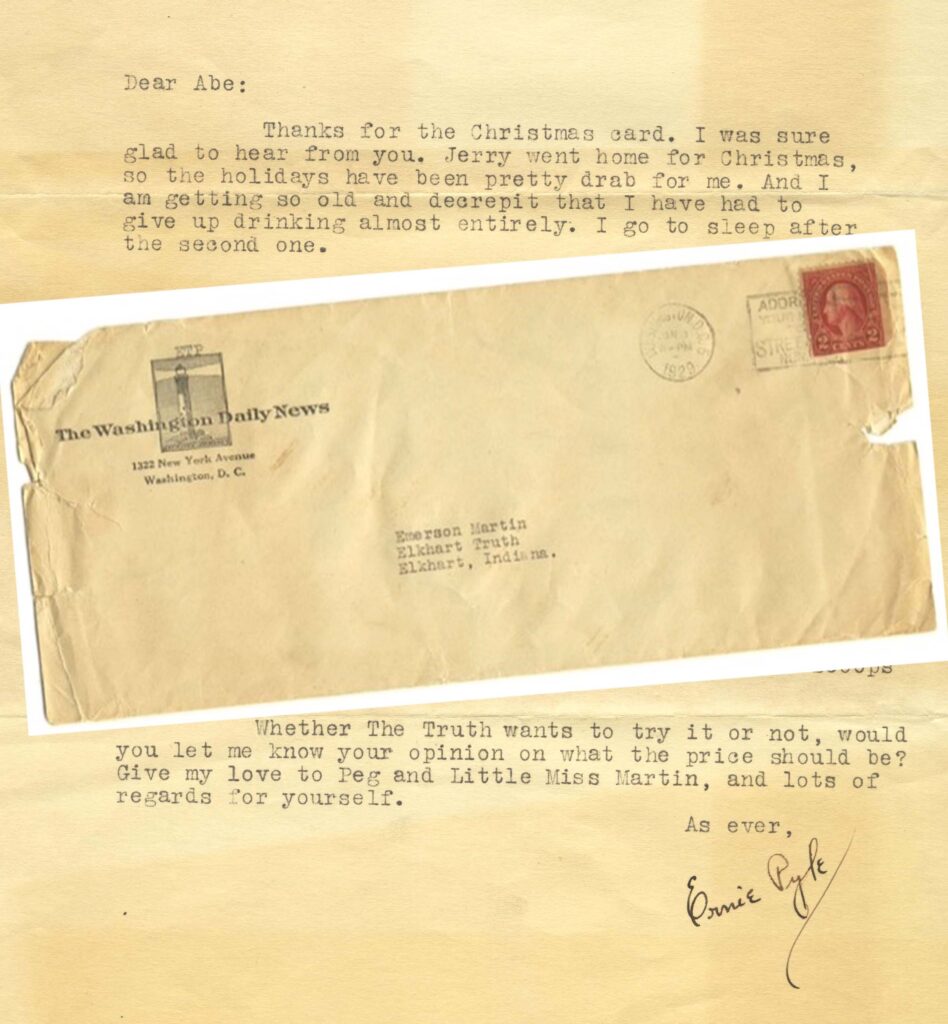

In October 1924, Martin left the Washington Daily News to become telegraph editor at The Truth. A month later, Pyle put a letter in the mail to his friend.

“I have been putting off writing from day to day, thinking maybe the next day I would get a letter from you, but I guess you aren’t going to write, so I will,” Ernie wrote. “… Things with me personally are about the same as usual. I come home every evening after work and read or write, and sometimes get pretty blue here all by myself, and then on the week-end and sometimes thru the week I go out with the gangs and raise hell.”

He updated Martin on the lives of people in the D.C. newsroom. He mentioned a girl “with whom I have fallen in love tra la” – she was Geraldine “Jerry” Siebolds, his future wife. And he wrote about how much he missed his friend.

“I hope you like your work out there and are satisfied and everything,” Ernie Pyle wrote. “I know the night you left here I hated to see you go worse than I ever did anybody in my life.

“I hope some day we may work together again, but such things usually dont happen. I dont know how long I will stick it out here. I may leave tomorrow, or I may get in a rut some of these days and stay here the rest of my life. I guess it doesn’t make much difference either way.”

‘Lots of regards’

In his next letter, Pyle wrote of a newsroom leadership shakeup “and we all came very near quitting.” He talked more about the people they knew in Washington and the happenings at other papers. He asked Martin to send a Coast Guard book long since promised.

Just one more letter from Ernie Pyle appears to have been kept by members of Abe Martin’s family, who shared them for this article. In his postmarked Jan. 1, 1929, note, Ernie responded to Abe’s Christmas card.

“I was sure glad to hear from you. Jerry went home for Christmas, so the holidays have been pretty drab for me. And I am getting so old and decrepit that I have had to give up drinking almost entirely. I go to sleep after the second one.”

He asked for Abe’s advice on a new column he was writing. He wanted to know whether The Truth would pick it up and how much they would pay for it.

In closing, Ernie wrote, “Give my love to Peg and Little Miss Martin, and lots of regards for yourself.”

Remembered always

Jerry Pyle, Ernie’s wife, battled mental illness through her life, and her health declined after Ernie’s death. She died of influenza on Nov. 23, 1945, just seven months after Ernie’s passing.

Abe Martin retired from The Elkhart Truth news desk in 1961. He spent his final years pursuing hobbies and remaining active with the American Legion. Involved from the early days of the Elkhart chapter, he eventually served as district commander of the veterans organization.

He died Jan. 3, 1969.

It’s not known what happened to the personal letters or cards Martin sent to Pyle. It’s possible the friends drifted apart and didn’t correspond much after the 1920s.

The news of Ernie’s death, though, gave Abe a reason to reconnect. He sent Jerry his condolences.

Her heartfelt response, which isn’t dated, has been pasted into a Martin family copy of “Brave Men,” by Ernie Pyle:

“Dear Abe,

“You’re mistaken – I did know you. When I read your letter, the years suddenly dropped away, and I remembered Ernie’s saddness when he told me about your leaving the News. I needn’t tell you how very close he felt to you then. Many times after that, when we were all gathered together on ‘our Saturday nights,’ the name of Abe Martin was often spoken, and you were somehow a part of each gathering.

“‘The best _ _ newspaperman I ever knew,’ I heard of you from Ernie, too often not to know you. I know he loved you deeply, Abe. There are things time cannot change. I think you were important to Ernie – a close association may be broken, externally – but your letter tells me both you and Ernie were better for having known one another. – Jerry”