History on tree bark

One of EPL’s smallest and oldest books holds the most mysteries

Looking for answers to questions long unanswered, a researcher came to Elkhart. The pursuit? Looking at a book in Elkhart Public Library’s special collection.

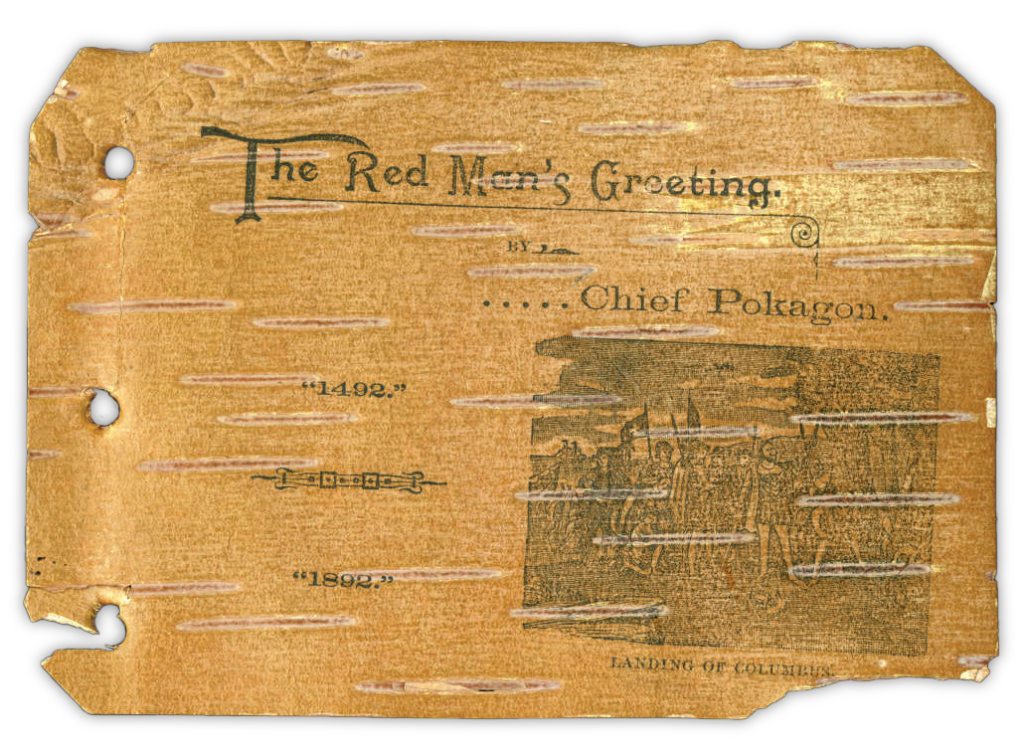

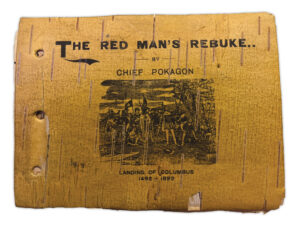

“The Red Man’s Rebuke” was written by Simon Pokagon, the leader of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi tribal nation. It was published in the late 1800s on birch bark paper.

The book is small and rare – only 30 or fewer known copies exist in public libraries around the country.

The work, and its author, remain a focus of contemporary research on unanswered questions. The message of the work continues to be relevant for indigenous people and activists, too.

The book and the research

Kelly Wisecup, an English professor at Northwestern University, focuses on 18th and 19th century indigenous literature. She visited EPL recently to see a copy of the Pokagon book.

“I’m trying to look at as many copies as I can so that I can see some of the differences,” Kelly says. “The pages are made out of birch bark, so they differ in the orientation of marks, the thickness, the quality of the pages.”

Kelly uses WorldCat, an online library search for mostly North American library collections. There, she can find libraries with copies of the publication, which was also produced under the name “The Red Man’s Greeting.” It was originally written for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

WorldCat is available in EPL’s Digital Library.

Some of her findings have been used by the Pokagon archives. Other researchers have benefitted from her work, like Blaire Morseau. She is an assistant professor of religious studies and associate professor of indigenous and native studies at Michigan State University.

Blaire was previously the archivist for the Pokagon Department of Language and Culture.

“With that book, specifically, he’s reclaiming Chicago as a native land. That is important because this (was) the Colombian Exposition, when the country was celebrating progress and ingenuity,” Blaire says.

“It’s politically poignant and speaking back to the idea that native peoples didn’t have a god and sacred things,” she says.

Kelly says the book’s political statements begin with the first words written.

Pokagon writes in the first paragraph:

“In behalf of my people, the American Indians, I hereby declare to you, the pale-faced race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in this Chicago city, wonder of the world.”

Kelly says, “It’s a brilliant critique. He’s pulling on this very popular history written by Washington Irving,” The “Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle” author also was a biographer of Christopher Columbus. “Pokagon is quoting (that) but also altering Irving’s words and critiquing the way that Irving represents indigenous people as simply these passive victims who were destined to fade away.”

Separating the work and the author

Blaire notes that Simon Pokagon is a controversial figure in the Potawatomi legacy due to Chicago lakefront property he sold without tribal consent. But the legacy of his writing has endured and made him popular among others.

“He’s definitely cast as a hero or a villain, depending on who you ask,” she says. “For some of the elders, he’s looked upon less favorably for some ethically dubious business dealings. But others think that he is the greatest and he was the political voice.”

Zada Ballew is a doctoral candidate in Native American history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She also is a Historical Consultant for the Native American Initiatives at the University of Notre Dame. She says she assigns “The Red Man’s Rebuke/Greeting” in every class she teaches as an important testament to indigenous resistance and protest.

Kelly says she teaches it for students to think about land theft and the territory where many Midwesterners live today.

“I felt like I had a responsibility to teach my students about whose lands they’re on. Not just knowing that history, but also being aware how land theft shapes how the city is today, maybe the inequities in the city today,” she says. “And to ask my students, how we can shape a future for Chicago or Elkhart that’s different from the past?”

Zada adds analyzing Simon Pokagon, the author, becomes more complex.

“I like to paint as full of a picture as possible. At the end of the day, he’s complicated,” she says.

The text though, remains important and relevant.

“This is a fiery protest. This text resonates with audiences today as much as it did back in 1893,” Zada says. “But the more I look into Simon, the more I dislike him. But with that dislike, I’m also trying to empathize with where he came from.”

Zada points out the upheaval Simon went through in his lifetime. He was born the same year as the Indian Removal Act of 1833. Tribes and bands of natives were forcibly removed from their lands or forced to sign treaties heavily favoring the United States.

“I don’t agree with everything that he did to get to where he was. But there’s no guarantee that the ‘Rebuke’ would be read today if he hadn’t been tied to those political figures in Chicago,” says Zada.

Those connections were forged during Simon’s work as the chair of the Pokagon Potawatomi business committee, an elected body that negotiated on behalf of the tribe. He was ousted from that committee sometime in the 1880s, but the reasons why that happened remain unclear, Zada says.

But by the time of the Colombian Exposition at the Chicago World’s Fair, he was billing himself as the authentic voice of the Pokagon peoples and its last chief. Zada says he wasn’t the last chief, but the choice was deliberate.

“He knew he wasn’t the last chief when he said it. … He knew what audiences wanted,” she says. “I also read it as (saying there’s) an urgency to his message.”

Remaining questions

Both Kelly and Blaire say much remains unknown about Pokagon’s book, especially about how it ended up in local libraries.

“It’s really interesting how some of those things come to rest in the library and then they lose their stories of how they got there,” Kelly says. “So what I’m doing is trying to piece together those stories.

“Who bought these books? Some were given as gifts, some people bought them at the Fair and donated them to a library. I’m really curious how a copy ended up here. It’s close to Pokagon’s homeland.”

Elkhart Public Library has no record of how its copy came into its collection.

Blaire recently compiled “As Sacred to Us,” a republication of all four of Pokagon’s birch bark writings. In that work, she included accompanying essays from modern scholars, all of Potawatomi descent. Much of Pokagon’s writing has deep metaphors that are the subject of much debate.

Viewing the ‘Rebuke’ today

Researchers encourage discussion of the ideas laid out by Pokagon in his work, as well as further study of potential outcomes.

Says Blaire, “In terms of his legacy, what I hope people can take away is that the research is not done. I hope that it inspires people to try to answer the questions and continue to research.”

Zada says she wants outcomes to focus on land acknowledgments and lifting up indigenous thinkers and leaders of today.

She says that following publication in 1893, audiences did think about its message. Ultimately, it led to one of the first land acknowledgment monuments known, which was built in 1909 in Plymouth, Ind.

“I want us to acknowledge that removal happened,” she says. “What tangible things do we put forward to make sure something like that never happens again?”

Kelly says this book being in Elkhart is an opportunity for local people to hear those ideas and think about the history of this land, which once belonged to the Pokagon tribe.

“Elkhart is on Potawatomi land. It’s a place that’s connected to Pokagon and his history and the history of this book,” she says. “I think the fact that it’s here is an opportunity for people in Elkhart to grapple with Pokagon’s critique.”

Zada says that analyzing the text, Simon Pokagon himself, and then the two together will give a better overall picture of the work and the tribal leader’s legacy.

“I think all three of those analyses really produce fascinating results,” she says.

Further reading about the World’s Fair and Pokagon

“Imprints: the Pokagon Potawatomi & the City of Chicago” by Dr. John N. Low

“Ogimawkwe Mitigwakre” by Simon Pokagon

“Ogimawkwe Mitigwakre” (American Indian Studies) (2011 Michigan State Press) by Simon Pokagon with additional analysis by Dr. John N. Low, Philip J. Deloria, Margaret Noodin, Kiara M. Vigil

“The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic and Madness at the Fair That Changed America” by Erik Larson

“Chicago’s Grand Midway: A walk around the the world at the Columbian Exposition” by Norm Bolotin

“Dibangimowin Pottawattamie ejitoiwin aunishnawbe” by Simon Pokagon

“The Potawatomi Indians” by Otho Winger

“The Potawatomi Indians of southwestern Michigan” by Everett Claspy

“A Lost Letter: Authenticating Simon Pokagon’s Literature” (2023 Chronicle- A Magazine of the Historical Society of Michigan) by John N. Low