Traffic headache lasted three years at the Johnson Street bridge

The traffic snarl on the Johnson Street Bridge lasted for years.

Politicians postured. Merchants called for help, and at least one store closed for good. State highway officials shook their heads in disbelief.

Work stopped to investigate cracks in the concrete supports. Seasonal weather caused delays, and so did bureaucrats. Three months were lost due to fish spawning.

The newspaper’s editorial joked the final ribbon cutting should take place at a park … to prevent another traffic tie-up.

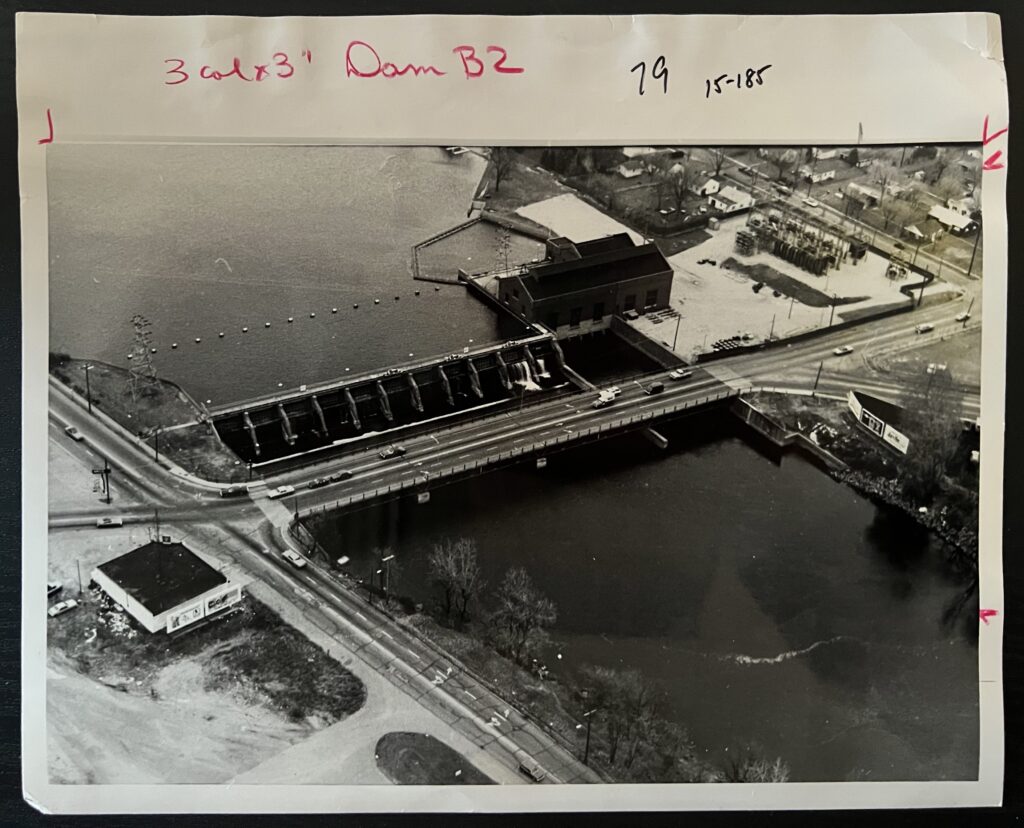

When the Johnson Street Bridge over the St. Joseph River fully opened in 1994, drivers finally had relief. The new travel lanes cut traffic congestion and simplified the route between downtown and Elkhart’s northeast side.

Two decades in the making, “The Bridge From Hell” became a three-year public works project to be remembered. And hopefully never repeated.

Fate vs. Johnson Street Bridge

More than 5,000 people signed a 1981 petition urging the commissioners to leave the bridge at least partially open during any construction project. The county made this possible by deciding to build a new structure to the west and then repair the old bridge, eventually doubling the traffic capacity.

Ten years later, work finally commenced. Kind of.

Less than 90 days into the project – May 3, 1991 – the front-page headline announced: “Bridge is safe … but Johnson Street span may need a new bid.”

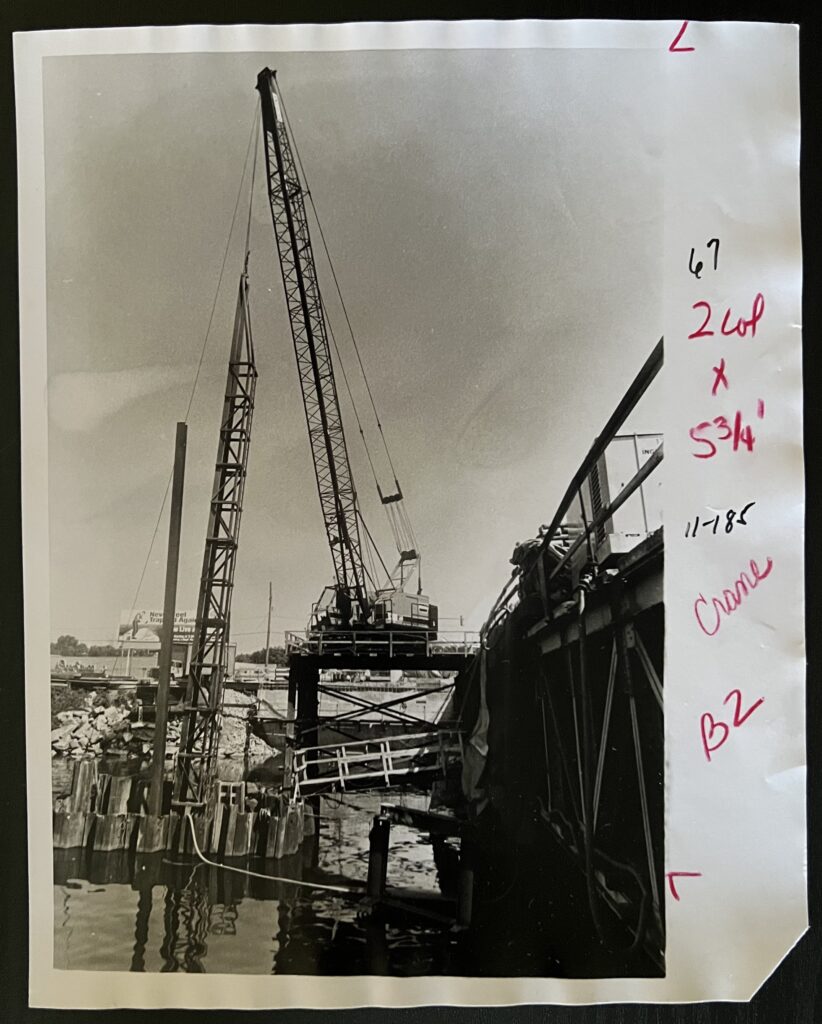

A crack observed in a concrete pier halted work for additional studying, and road officials put a strict 5-ton limit in place on the open lanes. A delay to build a temporary bridge would add millions to the cost and years to the disruption.

Elkhart Mayor Jim Perron called for the complete structure to be replaced. Commissioner Marsha Meyer said that suggestion was “irresponsible to the taxpayers.”

It wasn’t the only squabble, and certainly not the last delay.

The fish spawn cut into work until June 30. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission stepped in to halt the project at the beginning of August, saying the close proximity to the hydroelectric dam required its approval.

Year 1 of the project was a bust.

Nearby merchants reported overall business was down 30 to 40 percent.

“If I had the money, I’d like to sue the city, the county and the state. I have been at this location for 30 years. This is the worst business we’ve ever had,” said Andy Manos, owner of Andy’s Place, for a Truth report on Dec. 20, 1991.

Ankersen’s Women’s Apparel at Easy Shopping Place announced it was closing after the holidays. Dick Choler, owner of a car service and sales lot, said, “Sometimes it just doesn’t pay to go home. You might as well stay on this side of the river.”

Newspaper vs. decision makers

“Yes, everyone understands that the bridge is requiring unforeseen repair (but why was it not foreseen?)” The Elkhart Truth editorial stated on Dec, 22, 1991. “Yes, these things take time. But to ask businesses in the area to hold on until 1993 is an enormous sacrifice. Can the state speed up the schedule? They’ll probably say no. But amazing things can happen, if somebody in charge cares enough.”

Merchants wanted to hear from those in charge. County Commissioner Patsy Ronzone requested Mayor Perron attend a meeting with business owners in January 1992.

Perron wrote a pointed letter instead.

“Now that the repairs to the 80-year-old bridge are $2 million over budget and traffic is required to bear an unnecessary burden … you ask me to attend meetings with the affected property owners and stand shoulder to shoulder with you to take their justified expressions of displeasure, “ Perron wrote to Ronzone. “If the city is to have no authority and responsibility for this bridge, we will stay clear of it and let you handle your responsibility,”

Larry Murphy, The Truth’s opinion page editor, revisited all sides of the Johnson Street bridge debacle in his Feb. 20, 1992, editorial.

“Hindsight shows that the existing bridge should have been studied more thoroughly before the contractor arrived,” Murphy wrote. “… Lost time and additional cost raise the question of whether it would have been better to simply build another bridge in a different location.

“But the other options have drawbacks as well. In any new location, neighborhoods would have to be ripped open to provide connecting streets. Controversy over that promised to be greater than the agonies of building beside the dam at Johnson Street.”

City vs. County, the early rounds

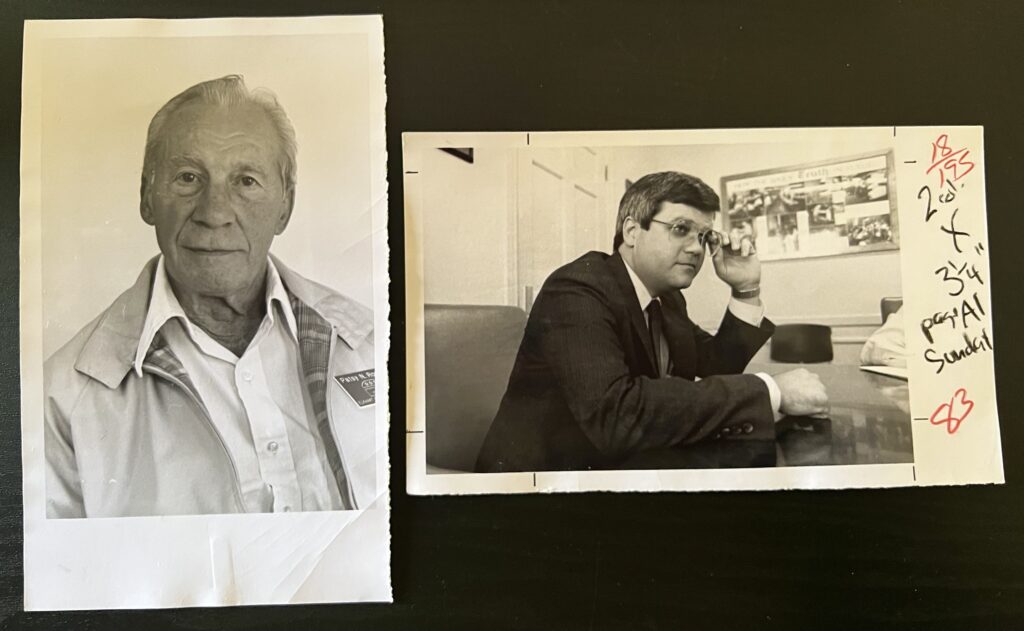

Mayor Jim Perron put into words what city residents were feeling as he delivered his ninth State of the City address.

People are “sick at heart of seeing and hearing politicians blaming each other for society’s ills when they should be working together to resolve them,” Perron said on Feb. 10, 1992. “Here in Elkhart … we can take pride in our efforts and our success; but we must be vigilant toward maintaining trust and partnership.”

But the divide between the mayor’s office and the county seat was wide. And it wasn’t just the politics of the day.

Going back to the late 1960s, it was clear the Elkhart County Board of Commissioners would not give up their decision-making authority on bridges.

Mayor John Weaver was seeking support for a new bridge east of downtown, at Bulldog Crossing, to ease traffic. People offered all sorts of ideas, including one to save money by using the steel from the Downtown Arch.

The commissioners, with a 2-1 vote, killed the idea in March 1969.

“(Johnson Street is) a problem they’re completely ignoring and don’t want to look at any part of it,” commissioner Ray Troyer told The Truth, adding the corridor needed major improvements to help traffic move.

Truth reporter Dick Robinett wrote Weaver “says he does not believe county government is sincerely interested in helping the city solve its problems. He says he has grown weary of having his proposals for city-county projects delayed.”

In 1971, the county commissioners and highway department started their pursuit of federal funds for the Johnson Street bridge. The feds rejected the first proposal. By then, Mayor Dan Hayes suggested a different east-side bridge, connecting Osolo Road and Simpson Street.

Again, an idea from City Hall floundered … and Johnson Street went unfixed.

City vs. County, the Perron era

Perron made it clear he was being ignored, or at least dismissed, on many matters by the county commissioners. He also fought what he considered to be dated concepts of government operations.

“It’s not a partisan issue for me,” the mayor told reporter Stephanie Davis Gattman in March 1992. “It’s a matter of practicality. I’m just trying to get things done. That’s all. … This is not a criticism of county government officials. (However, county is) too unwieldy to meet modern needs.”

For the same series of articles, Commissioner David Hess said, “First of all, (Perron) has been told many times that one of the most effective ways of dealing with the commissioners would be for him to deal with the county administrator (Dick Bowman). Which, to date, he has pretty much refused to do. Quite frankly, a lot of the letters he sends … I’m not sure we want to respond to them because I’m not interested in fighting.”

Perron was on board with Johnson Street improvements from the early days of his administration. In 1984, he said the bridge proposal “offers the greatest benefit at the least cost.” But in 1987, he publicly re-embraced the idea of the east-side bridge between downtown and C.R. 17.

The county charged ahead to go after federal funds. They would not consider a new crossing. This denial allowed Perron the flexibility to be critical. And the bridge project provided lots of room for that.

Ronzone vs. Ronzone

Unfazed by criticism, Patsy Ronzone carried the ball. At a meeting with officials from the Indiana Department of Transportation in February 1992, the commissioner declared people would drive across the new bridge by Dec. 31.

“The state officials shook their heads in disagreement,” The Truth reported. In the same article, INDOT operations staff member Dennis Kuehler said, “It is one of the most frustrating jobs in 20 years. The problems encountered on this job are unique.”

At the same event, Phil Schemerhorn, an INDOT public relations official and former Truth reporter, called Johnson Street “the bridge from hell.”

And the year was just beginning.

The bridge closed entirely for weeks in the spring as contractors replaced deteriorating steel trusses and joints – work which became necessary because cranes and other heavy equipment used the old bridge as a platform to work on the new.

WTRC-AM and the Perron administration partnered for on-air traffic updates. AIrport manager Phil Miller flew over traffic during peak times to report from the sky.

Traffic crossed the river again starting June 19, an occasion Ronzone marked with fanfare. He cut the ribbon on both ends of the bridge, and his wife made strawberry pies for the occasion.

But the new bridge still wasn’t open.

In October, Ronzone revised his prediction. The new lanes of the Johnson Street bridge, he said, would be done by June 30, 1993.

An ending at last

As rain and snow halted work in March 1993, Ronzone declared a new opening date – Aug. 15, 1993. A few months later, he announced it would be November.

That one kind of stuck, but not without one more bit of politics. City engineer Kent Schumacher and the contractor’s site manager pointed fingers in the newspaper about a late-game delay involving the placement of equipment and the inability for the city to finish its street approaches to the bridge.

Truth reporter Terry T. Mark covered the opening of the lanes on the new bridge for the paper on Nov. 25, 1993.

“A group of priests, ministers and rabbis gathered Wednesday afternoon to bless the new Johnson Street bridge, perhaps because one state official once described it as the ‘bridge from hell,’” Mark wrote. “Traffic became snarled again as Ronzone and other civic leaders cut the ribbon for the bridge. The sight of long lines of traffic waiting to cross the bridge seemed appropriate, though, given the history of the project.”

The Truth’s Thanksgiving editorial was not forgiving.

“It’s hard to feel that the bridge is really open while motorists still are dodging barricades as work continues,” Murphy wrote. “In a project marked by so many revised deadlines, Wednesday’s opening-that-wasn’t might strike cynics as appropriate.

“Truly, completion of the new bridge structure and the opening of its three lanes are welcome events. They give hope that renovation on the adjacent old bridge may go as scheduled so that the final two lanes can open before spring. That might be a time to really celebrate. But let’s hold the ceremony in the park and not have the traffic jam.”

The project’s final price tag was $6 million. The original bid was for $3.9 million.

On Jan. 25, 1994, The Truth reported all lanes finally were open. It was three full years after work started.